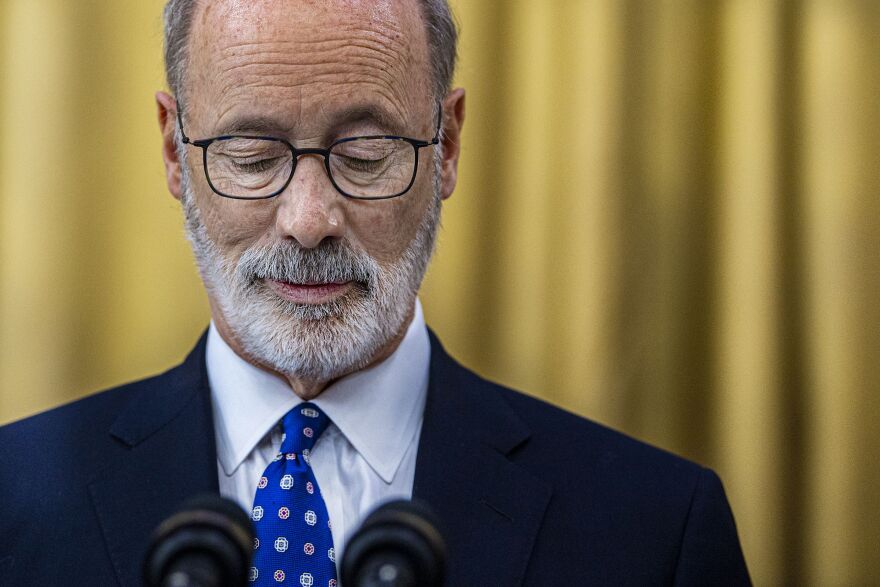

HARRISBURG, Pa. - Gov. Tom Wolf entered office eight years ago as a champion of government transparency.

- Gov. Tom Wolf entered office eight years ago as a champion of government transparency

- The legal office of Pennsylvania’s governor won’t explain why it paid private law firms at least $367,500

- Wolf’s administration has actively blocked efforts by news organizations to publicly release details of what cases, policies or subject matter the work involved

He posted his public schedule online. He banned members of his administration from accepting gifts. And he urged other state agencies, as well as the legislature, to do the same.

But when it comes to his office’s legal bills, the outgoing Democratic governor is all talk and little substance.

His Office of General Counsel — which refers to itself as “Pennsylvania’s Law Firm” — shields basic information about why it spends tens of thousands of dollars annually to hire private law firms, according to hundreds of pages of redacted records reviewed by Spotlight PA and The Caucus.

In fact, over the past year, Wolf’s administration has actively blocked efforts by the news organizations to publicly release those details, sharing only records that show which firms it hired, and how much those firms charged for some of its legal work — but, in nearly every instance, not what cases or policy and other matters the work involved.

The administration has argued, among other things, that the information is sensitive and that disclosing it could jeopardize its legal strategy — therefore making it exempt from the state’s open records law.

The lack of transparency has allowed Wolf’s Office of General Counsel to spend at least $367,500 over the past three years on a half-dozen law firms, in many cases without explaining why.

That total only includes payments to private law firms by Wolf’s Office of General Counsel, which usually handles litigation specific to the governor himself or other legal issues important to his office, such as disputes that may arise over his specific policies or the state budget.

The sum does not cover the myriad state departments under Wolf’s jurisdiction that also routinely hire private firms to handle matters specific to their agency. In years past, those agencies have spent between $30 million and $40 million per year on outside lawyers.

David L. Cuillier, president of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, said he finds it hard to believe that providing general descriptions of the work a firm is hired to do would somehow divulge sensitive details about a case.

“A simple general description will do, but apparently, Pennsylvanians will never know because they have to trust the government that all of the blacked-out descriptions included sensitive information,” said Cuillier, whose organization advocates for transparency in state and local governments and public institutions.

In a statement, Wolf spokesperson Beth Rementer said the governor has made transparent government “his highest priority.” Among his first actions in office, Rementer noted, was to begin competitively bidding legal contracts, and publicly post legal bids and awards.

She also said the administration prioritizes working with the public and the press, and that in regard to its legal bills, has “made available hundreds of pages of documents,” only redacting portions that “must by law remain confidential to protect either matters under investigation or to maintain attorney-client privilege.”

Records involving legal bills can be valuable guides to policies and matters that elected officials prioritize but do not necessarily want to be publicized. The decennial -– and highly partisan -– process of redrawing political maps, for instance, is one key issue for which state officials turned to outside law firms, spending millions of taxpayer dollars in the process.

Using Pennsylvania’s public records law, Spotlight PA and The Caucus in January requested invoices and other financial documents from the administration for spending on outside law firms from 2019 through 2021. The news organizations did so after several months of discussions with Wolf’s Office of General Counsel about the information they were seeking, and the best way to obtain it.

In response to the request, officials from the General Counsel’s office provided copies of 45 invoices, totaling $367,538, that outline the dollar amounts the six outside firms billed during that time period. The subject line in every invoice is redacted, as are portions of the invoices describing the work conducted by the private lawyers. The office did not turn over contracts or other documentation that had also been requested.

On every invoice, the officials redacted the short description (three or four words) of the work the private lawyers were hired to do.

In doing so, they cited exemptions under the state’s public records law that allow them to withhold information that falls under attorney-client privilege or that could reveal legal strategy or private communications between attorneys and their clients. They have also asserted that the invoices do not involve cases that are in the courts and have a public docket that summarizes proceedings in the case.

Deputy General Counsel Thomas P. Howell summarized the administration’s position in a recent email to Spotlight PA and The Caucus: “The [General Counsel’s] Office does retain firms to address specific legal issues that never result in litigation. The precise legal issues/questions that are asked of counsel are privileged (as they directly reveal communications between client/counsel seeking legal advice).”

He added: “That said, I believe that the invoices do shed light on the work that counsel performed (if not the precise legal question that they were asked to resolve).”

The news organizations appealed to the state’s Office of Open Records, an independently run agency that decides public records disputes, and soon after agreed to enter into mediation with the General Counsel’s office to resolve the matter.

But the office took months to produce only some of the additional records agreed to during mediation, and those it did turn over did not provide any further insight into why Wolf had hired outside counsel.

Specifically, the General Counsel’s office made available the underlying contracts they had signed with the six law firms — but those agreements were written so broadly that they effectively shielded the purpose of the representation.

For instance, the contract with one of the six firms, Myers, Brier & Kelly, states that the firm will provide “complex litigation services.” Another contract, with Blank Rome LLP, describes the firm’s work as providing “litigation and other potentially emergent legal services on an ad hoc basis.”

Spotlight PA and The Caucus ended mediation this fall — nearly six months after it began — because it was unproductive. Wolf’s General Counsel’s office in late September said it would provide more detail about the legal bills — but only did so in an email at 3:57 p.m. Monday, after the news organizations had reached out to the governor’s press office for comment.

The administration provided some additional information for why it had hired the six firms, but in only one instance was it clear what actual issue the work involved. In that case, the administration hired the private lawyers for assistance with reviewing and organizing a sudden influx of pardon applications.

In two other instances, the General Counsel’s office said the private lawyers were used for “specialized tax advice” and issues related to “federal rulemaking,” but did not elaborate.

The Office of Open Records issued a final opinion last month that sided with the administration, ruling the redacted information was not subject to disclosure.

But the records agency also made a pitch for transparency, saying it recognized that its opinion “means that the public is unable to fully understand why taxpayer-funded legal expenses have been incurred for these invoices.

“Agencies and third parties should be cognizant of that when preparing legal invoices so that the invoices permit the public to see how and why taxpayer funds were spent,” wrote Erin Burlew, the Open Records office lawyer who authored the decision.

Getting access to details on legal bills paid by state government agencies and the state legislature has a long and divisive history. But a landmark 2013 decision by Pennsylvania’s highest court ruled general descriptions of legal services, and the identity of who is being represented, are public information.

It’s not just the Wolf administration that appears to be flouting the spirit of that ruling. The state legislature spends millions in taxpayer dollars each year to hire private law firms through a closed-door process that, unlike other state contracts, is made with virtually no public oversight.

And like Wolf’s Office of General Counsel, legislative leaders also redact in full the purpose of many of their legal bills, a previous investigation by Spotlight PA and The Caucus found.

The news organizations, represented by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, have sued the state House and Senate in an effort to reveal why the two chambers hire outside lawyers. The case is before Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth Court, with oral argument scheduled in the matter on Dec. 12.

Gunita Singh, a staff attorney for the Reporters Committee who is not involved in arguing the case next week, said agencies in Pennsylvania have an explicit duty to narrowly construe exemptions to disclosure. That rule, she said, applies even when dealing with information subject to a privilege, because Pennsylvania’s open records law contains an express presumption in favor of disclosing records to the public.

Beyond that, the law does not prevent a government agency from making a record public, even privileged ones, in order to further transparency.

She said Wolf’s General Counsel’s office appears to be shielding even the most generic information about why the government is spending money on private law firms. There are specific criteria that must be met in order to withhold records under the attorney-client privilege; if the information falls outside of those specific metrics — as generalized descriptions likely will — it must be disclosed.

“This is especially true given the heightened public interest in these records,” she said.