ALLENTOWN, Pa. — Mayor Matt Tuerk doesn’t want to be a mythical Johnny Appleseed — planting and planting and planting before moving on, not sticking around for the hard work of maintenance.

- Allentown Mayor Matt Tuerk wants to boost tree equity in the city

- Tree equity is the measure of healthy, shade-giving trees throughout an entire community

- Community engagement and education are key to boosting equity citywide

“We're gonna talk about the tremendous benefits that come from having trees, and strongly encourage [residents] to plant in their neighborhoods and try to reduce any financial or legislative barriers that exist to them planting,” Tuerk said during a tour of one of the most inequitably planted neighborhoods in the city.

“But we're also gonna listen to the people.”

Listening is key, as community engagement and education are two the top hurdles Tuerk, as well as municipal officials across the Lehigh Valley and the rest of the country, must overcome in order to increase tree cover in a way that benefits all residents, regardless of socioeconomic status. While planting trees isn't an overnight solution, experts said strategic, equitable planting is a long-term investment to make communities more sustainable, cooler and boost the health of not only the environment, but the people who live there too.

During a short walk Wednesday afternoon from Fearless Fire Company in the 100 block of West Susquehanna Street, past Roosevelt Elementary and onto Third Street, beads of sweat started to form on Tuerk’s forehead. It felt hotter than the mid-70s temperature reading.

“We all have like a little bit of sweat from just walking two blocks, right?” Tuerk asked. “These should be shady streets — there's nothing about this neighborhood that says we shouldn't have trees.”

These should be shady streets — there's nothing about this neighborhood that says we shouldn't have trees.Matt Tuerk, mayor of Allentown

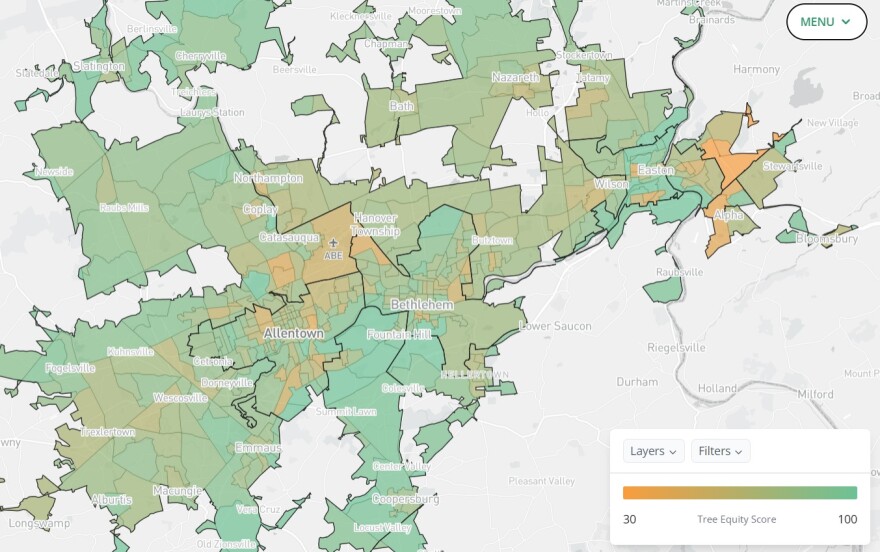

Tuerk picked the neighborhood because it’s one of the least equitable in the city for tree coverage. Measured by nonprofit American Forests, the area scored a 53 out of 100 for tree equity, with only 8% canopy cover.

It’s a stark contrast to other city neighborhoods, creating a patchwork pattern of varying tree density that exists not only in the city, but across the Valley. Tree cover is only one layer of the problem — experts and academics have been studying the correlation between tree cover and socioeconomic status.

Their findings bring into stark reality a larger issue of equitability. Areas with dense tree cover are more likely to be populated by white residents with higher incomes, and the reverse is also true.

What is tree equity?

The first time Anita Forrester, a professor at Northampton Community College and leader of Climate Reality Project Lehigh Valley, heard the term “tree equity,” she was unsure what it meant.

Then, she realized it’s something she, as well as other environmentalists, have been talking about for several years — it had just been given a name.

“The reason why trees are important is that they have, of course, a health impact, a cooling impact, a social impact on the community,” Forrester said, noting that trees can cool an area by between 20 and 45 degrees on a hot day. “ … If you have trees, you create a community. People go outside, sit under the trees, and have a conversation. You build the community who's going to be vested in the community, as well.”

Trees can act as “tiny little air scrubbers,” improving residential health, as well as absorb carbon dioxide — a major contributor to climate change.

Tree equity, or the measure of healthy, shade-giving trees throughout an entire community, in recent years has become a key part of environmental justice initiatives. The American Forests tree equity map has cataloged the entire country, including the entire Valley.

“Trees are more than scenery for our cities,” according to the nonprofit’s website. “They are critical infrastructure that every person in every neighborhood deserves — a basic right that we must secure. But a map of tree cover in America’s cities is too often a map of income and race.

“That’s because trees often are sparse in low-income neighborhoods and some neighborhoods of color. Ensuring equitable tree cover across every neighborhood can help address social inequities so that all people can thrive.”

Karen Beck Pooley, a professor and director of Lehigh University’s environmental policy design program, studies housing and neighborhoods, including quality-of-life issues. It was a couple years ago when one of her students, Samantha Roth, discovered a correlation between Allentown’s trees and hotter temperatures in different parts of the city.

“Wherever you have more asphalt, more buildings, buildings closer together, there's less room for greenery, which has been a challenge in cities forever,” Beck Pooley said. “In those places, since they absorb more heat, they tend to get hotter … it's one of these just like, rich get richer, poor get poor kind of situations, where in places where you're more likely to find air conditioning, more likely to find trees, you'll have less of that heat effect.

“And the opposite on all of those fronts is true in other parts of town.”

The pair went on to give a presentation of the findings, illustrating that Hispanic residents are far more likely to live in neighborhoods with less tree canopy and more heat.

‘A tree is a ridiculous luxury’

During the tour with Tuerk, he noted the tree equity map was a good starting point and a pivotal tool to help move the city forward. Having the ability to buy, plant and maintain a tree is a luxury, he said.

“In the poorer neighborhoods, where people might not have the same income, a tree is a ridiculous luxury,” he said, adding that officials cannot just give out trees expecting residents to know how to care for them and burden them with the cost of that maintenance. “We want to invest in engagement in places like this, to ask people what they think about trees.”

Many residents cite similar concerns. For example, city homeowners are mandated to maintain sidewalks. Who would bear the cost if growing tree roots causes the cement to buckle? Who is buying the tree? Is it a native species? Who is maintaining it? What happens if it dies?

“Trees can be a real pain in the neck sometimes if, going into it, it's not clear who's going to be responsible for what, and there's not the right kind of collaboration and cooperation when it comes to any consequences like sidewalk buckling that might come from them,” Beck Pooley said. “ … On one hand, it's profoundly simple – trees. And on the other hand, it gets complicated pretty fast, but still eminently possible.”

While Tuerk said he was unsure if the city was in a position to take over responsibility for sidewalks with tree cuts, he’s been working on solutions to mitigate any barriers in order to move towards tree equity in the city.

“There is a famous saying, which is, ‘The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, and the second best time to plant a tree is today,’’ Tuerk said. “Just do it — get trees in the ground, in a place where it makes sense, picking species that make sense.”