BETHLEHEM, Pa. — There’s nothing wrong with being a tourist, Marten Edwards said, especially when it comes to visiting insects during a natural phenomenon.

“The people who are going to actually take the trouble to do that are really going to be respectful of nature, so I think it's a wonderful thing,” said Edwards, a Muhlenberg College biology professor.

“And when you're in that environment and see what an awesome power it is — maybe it's not for everybody, but I really find it an awesome experience, like the old-fashioned use of the word awesome, inspiring of awe.”

Lehigh Valley residents interested in this year’s periodical cicada emergence will have to share that traveling spirit.

For another year, the Valley won’t see any cicadas, known for spending more than a decade below ground before surfacing in large groups to sing, mate and die — continuing their lifecycle.

“A lot of the maps are exaggerated, because they don't have the information about how many there were there,” Edwards said.

“If you see one cicada, and the whole county gets coded for ‘There are cicadas here,’ it's going to make your map look like it's a much bigger distribution than it really is.”

What are cicadas?

Cicadas are a type of insect categorized with others that have sucking mouthparts, which they use to feed off tree roots.

There are two main types: the periodical and the annual.

Annual cicadas, which are black and green, emerge each year, as their name implies. They show up around the Fourth of July in the Valley, generally until about August.

Periodical cicadas emerge in 13- or 17-year cycles. Black with red eyes and orange wings and noticeably smaller than the annuals, periodical cicadas are triggered to emerge when the soil temperature reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

“By the Fourth of July, they'll be gone. And then there'll be just a load of free fertilizer that's going to really give a rush of growth to the trees next year.”Marten Edwards, Muhlenberg College biology professor

They belong to the genus Magicicada — “literally, because it's kind of magical, the way they show up,” Edwards said.

However, not everyone has a favorable opinion.

“A common name for them is locusts,” Edwards said. “And that was given to them because they come out in huge numbers, like a plague of locusts. But they are definitely not locusts.”

Periodical cicadas emerge in huge numbers as a defense mechanism, illustrating safety in numbers.

After spending immature stages underground, sucking the liquid from tree roots, they emerge, depending on the cycle.

The males scream, or sing, to attract a female. After they mate and the female lays eggs, usually on a tree branch, they die.

“By the Fourth of July, they'll be gone,” Edwards said. “And then there'll be just a load of free fertilizer that's going to really give a rush of growth to the trees next year.”

Where will they emerge?

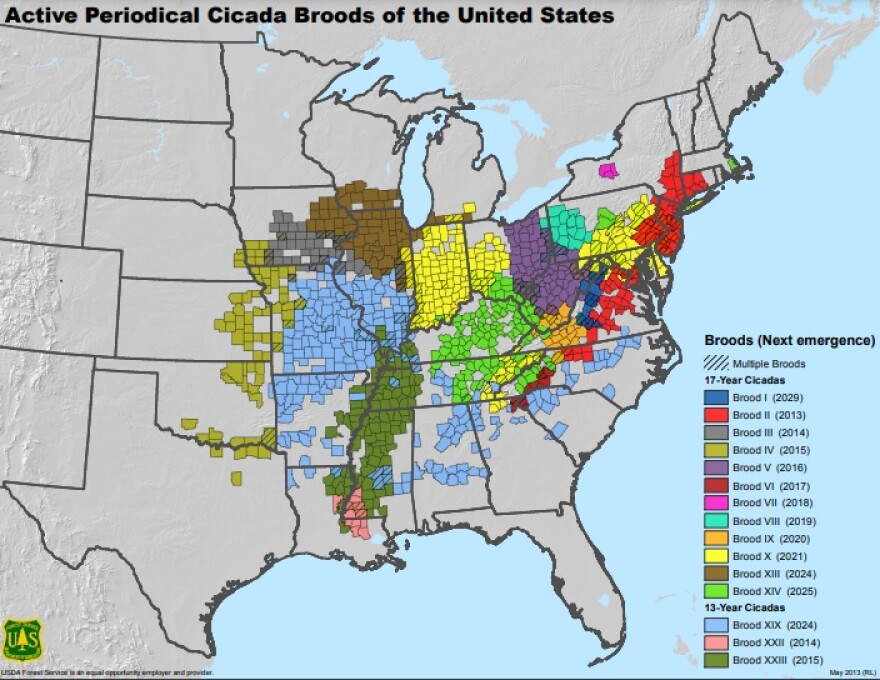

In Pennsylvania, the cicadas are on a 17-year cycle, categorized into broods.

“The broods are what year they come out,” Edwards said. “So they're the same species, but in different parts of the state, you will be seeing different broods which come out at different times.”

This year, Brook XIV, “The Great Eastern Brood,” is set to emerge in patches, including a large swath from northeast Georgia to southern Ohio, as well as areas of Long Island, Cape Cod and in central Pennsylvania, around State College.

They last emerged in 2008.

However, another phenomena might have periodical cicadas popping up in parts of Chester and Berks counties.

“If cicadas come out too late, for some reason, they will come out four years too late,” Edwards said. “There may be quite a few, but they will be holdouts from the huge number that came out in 2021.”

Those holdouts are from Brood X cicadas, which emerged just south of the Valley four years ago. They won’t appear again in large numbers until 2038.

Any holdouts are generally “doomed,” Edwards said, because they don’t emerge in large enough numbers.

How to find them

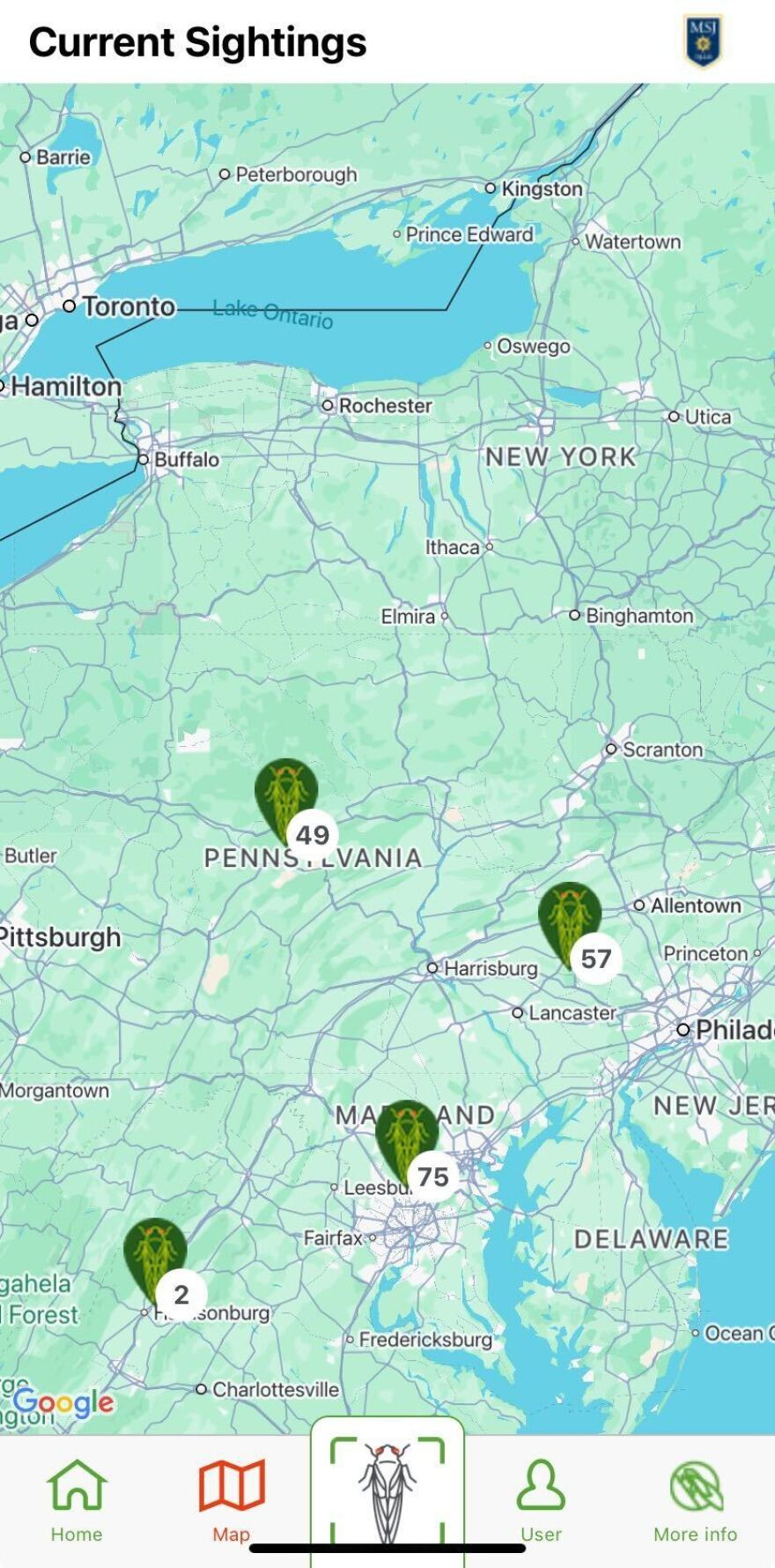

Residents can use Cicada Safari, a free app created at Mount St. Joseph University, to find out where cicadas have emerged.

Users can upload pictures and locations of cicadas they find. Once approved, they’re added to the app’s map.

So far, cicadas have been spotted around the central and southeastern parts of the commonwealth, according to the app’s map.

“It's actually really useful,” Edwards said. “There's only a few people who actually study cicadas, and so having thousands of people contributing the information is just so much more useful than just a few people who can't possibly cover that much ground.

“And sometimes, if there's a lot of reports from the public in a particular area, it can alert scientists to go and make new scientific discoveries that might not have been on their radar if there wasn't this citizen science.”

While residents might dread the emergence for one reason or another, Edwards said the cicadas aren’t harmful.

“They don't sing at night,” he said. “Just go inside if it's so noisy during the day. But really, there's no harm that they're going to do.

“The only possible problem is, if you've just planted a tree, you probably want to cover it with some netting to make sure it doesn't get its twigs at the edge damaged.

"But really, that's the only concern that a person should have.”