BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Trillions of periodical cicadas will emerge this year to scream, mate and die—just not in the Lehigh Valley.

“We could maybe plan a cicada road trip to see them,” said Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards, chuckling during a recent phone interview. “Sorry to disappoint, but this is not going to happen in Pennsylvania.”

It’s a special year for cicadas, insects known for their loud mating songs, with two adjacent broods expected to co-emerge for the first time in 221 years, slightly overlapping in north-central Illinois.

While some have called 2024 “the year of the cicada” or are expecting an “insect apocalypse,” the emergence isn’t anywhere near this region, experts said, and over-hyping the natural event works to attach more unwarranted stigma to these harmless, native insects.

“I see the words like ‘cicada apocalypse,’ and I get it that people want to be dramatic about it,” Edwards said. “But that sounds like a bad thing.

“It's really a marvelous thing to see these cicadas coming out and such huge numbers.”

Periodical and annual cicadas

Annual cicadas, like their name implies, come out each year, and are black and green.

“You don't start to even see [annuals] until the Fourth of July,” Edwards said. “And they'll be doing their thing way up until August. They’re actually, maybe, 3 to 5 years old when we see them, but, since they come out every single year, we call them annual cicadas.”

Periodical cicadas, which emerge in 13- or 17-year cycles, are black with red eyes and orange wings and are noticeably smaller than the annuals. They are triggered to emerge when the soil temperature reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit, which can be earlier in the year than the annuals.

“They both spend their entire immature stages underground, sucking the xylem, basically the liquids from roots of trees,” Edwards said.

When they emerge, the males scream, or sings, to attract a female. After they mate and the female lays eggs, usually on a tree branch, they die — continuing the cycle.

“The eggs hatch in six weeks, and young cicadas, or nymphs, fall to the ground where they burrow into the soil and spend the next 17 [or 13] years feeding on small roots, without causing significant damage,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “At the end of this time, usually in May and early June, nymphs crawl out of the soil and climb up tree trunks or other vertical objects where they shed their skins and emerge as adults.”

Periodical cicadas emerge in such large numbers on purpose, as a safety strategy.

“They're tasty. They're completely unable to protect themselves. They're not great at flying. They're basically just asking to be eaten, and so their strategy is to come out in such massive numbers all at once that the predators can't possibly eat them all.Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards

“They're tasty. They're completely unable to protect themselves. They're not great at flying,” Edwards said. “They're basically just asking to be eaten, and so their strategy is to come out in such massive numbers all at once that the predators can't possibly eat them all.

“They've worked out that the ones that all came out with the safety and numbers, they survived. And then that ability to come out all at the same time kind of set in as their pattern of doing it.”

Where will the cicadas be in 2024?

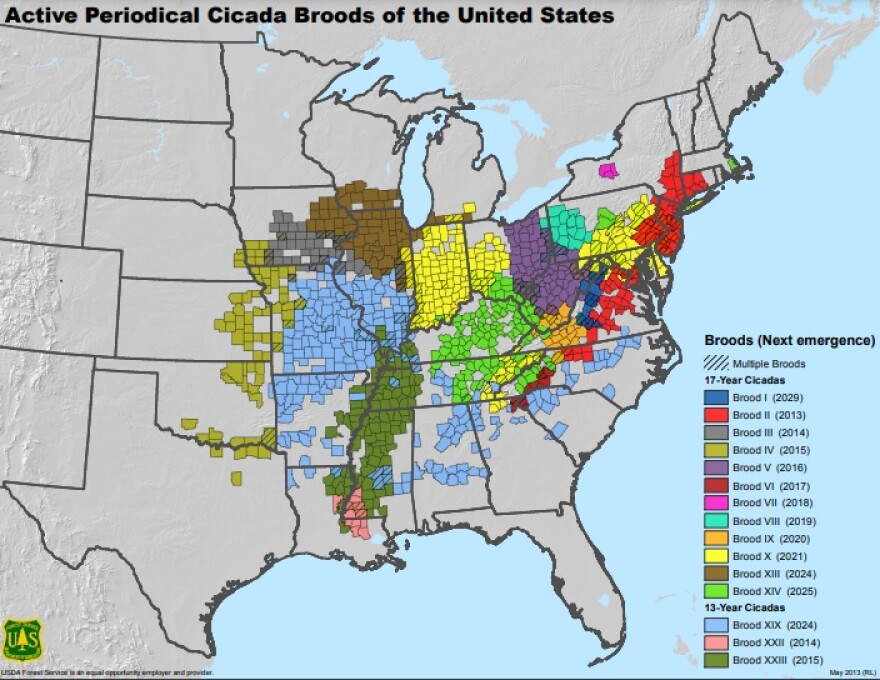

Scientists have studied emergences since the early 1800s, the different broods fitting together like puzzle pieces on a map of the eastern U.S. By tracking these insects, researchers can predict where and when they’ll be seen next.

This year, 13-year Brood XIX, “The Great Southern Brood,” will co-emerge with 17-year Brood XIII, also called “The Northern Illinois Brood.” The former has the largest geographical distribution of any other broods across the country, with records along the East Coast from Maryland to Georgia and in the Midwest from Iowa to Oklahoma.

It’s an exceptional emergence for several reasons, according to researchers at the University of Connecticut:

- For the first time since 2015, a 13-year brood will emerge in the same year as a 17-year brood.

- For the first time since 1998, adjacent 13- and 17-year broods will emerge in the same year.

- For the first time since 1803, Brood XIX and XIII will co-emerge.

- Residents will be able to see all seven named periodical cicada species as adults in the same year, which will not happen again until 2037.

- Residents will not see all seven named species emerge in the state of Illinois again until 2041.

But, just because they cover a wide range doesn’t mean residents will be overrun.

“It's not that it's like the entire whole area is going to be completely crawling with cicadas — it's a little bit of an urban legend. Sometimes there's a lot of hype before they come, so people think that there's going to be cicadas crawling out of every single tree, but not necessarily.”Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards

“It doesn't mean that they're super intense everywhere they come out,” Edwards said. “People get the idea that cicadas when they come out, they're super, super dense and absolutely everywhere. And that's not really true.

“It's not that it's like the entire whole area is going to be completely crawling with cicadas — it's a little bit of an urban legend. Sometimes there's a lot of hype before they come, so people think that there's going to be cicadas crawling out of every single tree, but not necessarily.”

Because cicadas need trees as a food source, there won’t be cicadas where there aren’t trees, like farmland or more developed urban areas.

“Wherever they’re coming out, that tree has to have been around for 17 years, or must be very close to another tree that they can hop on to that root,” Edwards said. “But they don't really move around much from tree to tree, because they have to crawl underground.

“It's not like they can crawl 50 feet away to another tree.”

When will the Lehigh Valley hear the cicadas sing?

Researchers aren’t expecting any cicadas to be near the Valley, or even the state, during this year’s emergence.

“In Pennsylvania, we're not gonna see a single cicada unless somebody brings it back in their car."Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards

“In Pennsylvania, we're not gonna see a single cicada unless somebody brings it back in their car,” Edwards said.

The last time periodical cicadas were near the Valley was in 2021, when Brood X, or “The Great Eastern Brood,” emerged. The next time that brood is expected to emerge is 2038.

But the next emergence is right around the corner.

“Our next big cicada year is going to be next summer, that's Brood XIV,” Edwards said. “A lot of them are going to be in the middle of the state, and some of them are going to be south of us, towards the Lancaster area — wherever they come out is going to be different than Brood X.

“So, if you saw cicadas in 2021, you probably won't see them in 2025.”

Even if this year’s emergence is over-hyped, spreading the word about cicadas, and increasing residents' knowledge of the environment around them, is a good thing.

“I think, probably thanks to media, there's a lot more positive attention than negative attention, and the people now are more excited about them,” Edwards said. “In the old days, it was like, ‘Oh, these super annoying insects are gonna make a lot of noise and they're gonna bother us and ruin our weddings.’

"I think that they're not seen as anything to be worried about — they're not going to hurt your plants, or sting you or bite you. I think that probably, in general, there’s more positive excitement about them than doom and gloom — that's my hope.”