BETHLEHEM, Pa. — The Asian longhorned tick, an invasive species known for females that can reproduce without a male, has spread to the Valley.

“They have probably been in the Lehigh Valley since before 2017, but not at numbers that captured anyone's attention,” Marten Edwards, a Muhlenberg College biology professor, said.

“My research team found a few of them in 2020. Each summer, we collect about a thousand deer [blacklegged] tick nymphs, but only a handful of longhorned ticks.”

With warmer weather finally forecast for the Valley, and summer right around the corner, tick season is in full swing.

“If it really is a longhorned tick, then take it as a reminder to up your tick prevention game; the next bite might come from a deer tick.”Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards

While residents might be more familiar with blacklegged ticks, those most often associated with Lyme disease, there are several species of ticks that now call the Valley home.

They include the invasive Asian longhorned tick.

“They look pretty much like other ticks, including deer ticks,” Edwards said. “They don’t have visibly long ‘horns’ or any other features that make them easy to identify.

“If it really is a longhorned tick, then take it as a reminder to up your tick prevention game; the next bite might come from a deer tick.”

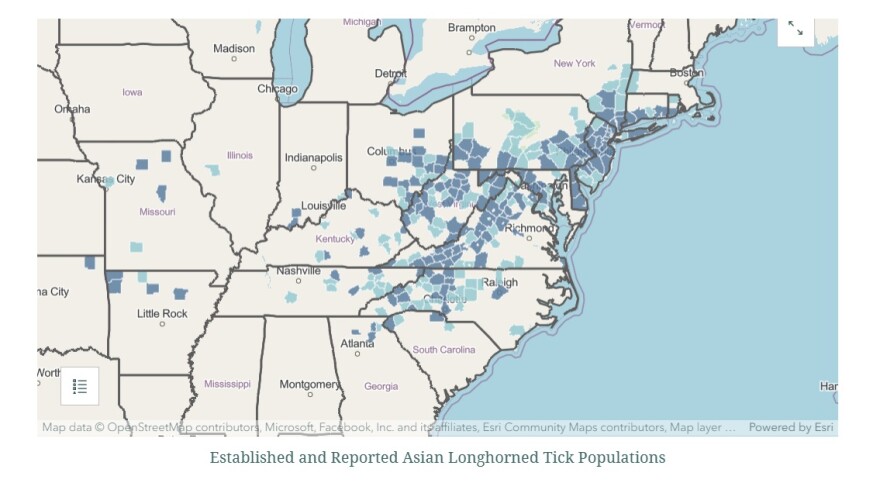

The Asian longhorned tick has been recorded in almost half of U.S. states, mainly along the East Coast, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Populations in the United States are parthenogenetic, according to the USDA.

That means an individual female can lay eggs without mating — essentially cloning herself to create the next generation.

'Researchers need to keep on top of it’

Unlike blacklegged, or deer, ticks, Asian longhorned ticks aren’t known to transmit human diseases, Edwards said.

“They have not been shown to transmit any human diseases in the United States, and they are not capable of transmitting Lyme disease,” Edwards said.

“This doesn’t mean things won’t change, and researchers need to keep on top of it.”

The state Health Department last year launched an online dashboard with information about tick-borne diseases, including Lyme disease.

"Every year in the Valley is a bad tick year."Muhlenberg College biology professor Marten Edwards

The disease, with its characteristic rash, can cause fever, headaches, irregular heartbeats and more.

So far this year, there have been 26 Lyme cases recorded in Lehigh County, and 29 in Northampton County, according to the dashboard.

But there’s no use speculating if this year will be worse or better for ticks than years past

"Every year in the Valley is a bad tick year," Marten said during a 2024 interview with LehighValleyNews.com.

Here's LehighValleyNews.com’s interview with Edwards. Some answers were edited for style and clarity.

Q: What is a longhorned tick?

A: Longhorned ticks (also known as the Asian longhorned tick) made headlines in 2017 when they were found in large numbers on a sheep farm in New Jersey. The invasive species probably arrived about 10 years earlier and went unnoticed.

It has since spread to at least 21 states. Genetic evidence suggests that it was introduced from Asia. It has been established in Australia, New Zealand and other Pacific nations for more than a century.

This tick is unusual in that it does not require males for reproduction. A single female can lay around 2,000 eggs. This makes the tick very easy to introduce to new places, since it only takes one tick.

In nature, longhorned ticks primarily feed on deer, but will feed on smaller mammals and birds. They also feed on livestock, including sheep, horses and cattle.

They typically do not bite people, although a few human bites have been reported. They are not yet known to transmit any human diseases here in the United States, but they do transmit a pathogen that causes a serious disease in cattle.

Populations of this tick can become very large, and animals can be harmed by the loss of blood during an especially intensive infestation.

Q: What does its lifecycle look like?

A: Blood-fed female longhorn ticks lay their eggs in mid-summer, which hatch about a month later. By late summer and into the fall, the larvae look for their first blood meal. After feeding for the first time, they will molt to the next stage, called nymphs. The nymphs enter a dormant state for the winter and start to look for their second meal in the spring and early summer, just like deer ticks.

After they feed, they will become adults. The adults will start to look for their third and final blood meal in late July. A few weeks after this final feast, they lay their eggs and die.

Q: What kind of environment does it thrive in?

A: They prefer grassy pasture habitats near forests, but can also be found in forests. They need humidity, so they do not thrive in mowed lawns. During the winter, they enter a state of dormancy, so freezing temperatures do not bother them.

Q: Do they have the same "season" as deer (blacklegged) ticks?

A: Unlike deer ticks, which need two years to complete their life cycle, longhorn ticks can complete their cycle in one year.

Q: Do methods for protecting yourself from deer (blacklegged) ticks work for longhorned ticks?

A: Fortunately, yes. All of the good habits you already have with protecting yourself, your family and pets from deer ticks also work with longhorned ticks.

Q: What should you do if you get bitten by a longhorned tick?

A: The best method is to use a pair of very fine forceps and gently pull the tick out right where its mouthparts meet the skin, and clean the site carefully to prevent an infection.

If the tick has been biting for more than 24 hours, show it to a medical professional to make sure it is correctly identified as a longhorned tick.

For more information on tick prevention, go to the state Department of Environmental Protection’s website.