SALISBURY TWP., Pa. — Each year, more than 26 million children ride the nation’s 480,000 school buses.

Statistically, Sgt. Bryan Losagio said, it’s the safest way for them to get to school, but it’s not without risk.

That risk is highest, Losagio said, when children are getting on or off the bus 7-8 a.m. and 3-4 p.m.

That’s why, at a training session for bus drivers Tuesday at Salisbury Township Police Department — less than a week before the start of a new school year — Losagio emphasized one simple but crucial formula: The 1-10 rule.

“If anybody takes anything away from today's presentation, this is absolutely crucial. It's the 1-10 rule,” said Losagio, the department’s traffic safety coordinator.

"If we follow this rule, we will have nothing but good violations.”

The violations to which he referred involve automated school bus camera enforcement.

“Statistically, school buses are the safest way for children to travel to and from school, but fatalities still do occur."Salisbury Township Police Sgt. Bryan Losagio

In Pennsylvania, drivers who illegally pass a school bus with flashing red lights and an extended stop arm can be caught on video and face civil citations carrying a $300 fine.

Police see video of the alleged violation and either approve the citation (a “good” violation) or reject it.

And the 1-10 rule? It works like this: for every 10 mph of the posted speed limit, a school bus driver should leave the yellow warning lights on for one full second after the bus comes to a complete stop, before extending the stop arm and activating red lights.

In a 30 mph zone, that means the driver counting “one, two, three” before flipping the switch. On a 40 mph road, it’s four seconds. At 45 mph, four and a half.

Those few seconds, Losagio said, can mean the difference between police reviewing video evidence of a good violation, or one with a questionable call that might get thrown out.

More importantly, it can mean the difference between a safe child and a serious crash — or worse.

“Statistically, school buses are the safest way for children to travel to and from school, but fatalities still do occur,” Losagio said.

“For the bus drivers, the highest risk for a child is when he or she is first getting onto the school bus or exits the school bus.”

Why seconds matter

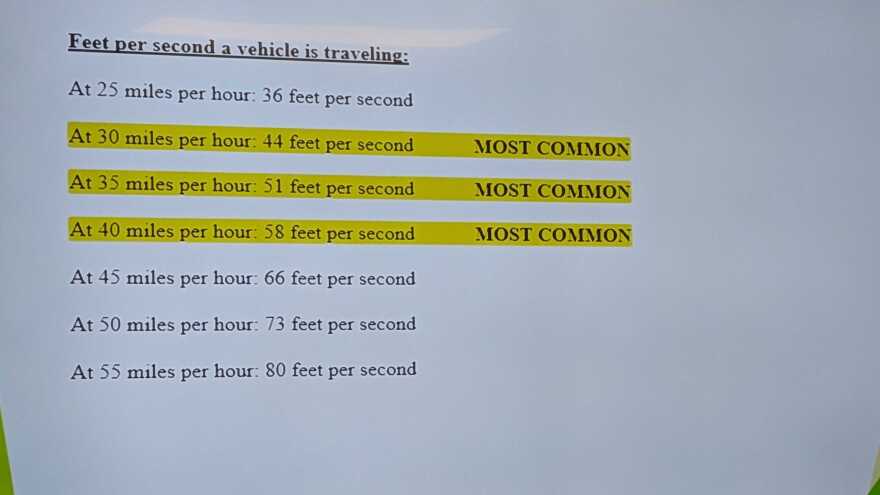

On Tuesday, Losagio walked drivers through the math: At 25 mph, a car covers 36 feet per second. At 45 mph, it’s 66 feet. At 55, it’s 80.

It means a motorist approaching a stopped bus at highway speeds can travel the length of a football field in just over four seconds.

By giving motorists fair warning with the 1-10 rule, bus drivers allow approaching drivers the reaction time they need, Losagio said, to slow down safely and stop, or be in clear violation if they don’t.

“In many instances, a traffic light on Pike Avenue or Cedar Crest Boulevard will display a yellow light for one second for every 10 miles per hour,” Losagio said.

“This allows a motorist time to see the yellow light and judge the amount of time he or she has to decide to stop or proceed.”

Fairness for drivers, safety for kids

For Salisbury police, the rule isn’t just about safety — it’s about fairness and consistency.

“This program needs to be fair and consistent," Losagio said, citing public support for school bus camera enforcement. "Very consistent enforcement will equal a successful program.”

He stressed that questionable violations — those where a motorist may not have had enough time to react or faced visual clearance issues — can undermine trust in the entire program.

He listed other factors beyond extremely brief activation of yellow warning lights, or a bus moving with its stop sign out.

He said wet or slick roadways, curved roadways, sun glare or larger vehicles blocking a motorists’ view all have to be considered before approving a violation.

“When I watch that video, if I have to look at it three times, it's not going to get approved," he said. "Because I give the benefit of the doubt to the driver.

“I should be able to watch that video and just say, 'No question at all.'”

That’s why the “gold standard” stops are those where bus drivers followed the 1-10 rule, giving motorists ample time to see, react and stop — or face that $300 citation if they don’t.

Balancing enforcement, discretion

During the training, bus drivers raised concerns about equipment quirks and real-world obstacles, including a multi-position switch that can be left in a middle or neutral position and potentially trigger red lights too soon.

Losagio acknowledged those challenges, but reinforced the importance of sticking to safe, consistent procedures.

“As a bus driver, consider allowing an approaching vehicle that does not appear to be stopping to simply pass the bus before activating the red lights and stop sign,” he advised.

“At the end of the day, you may be right that the vehicle should have stopped,” he told the drivers before showing them video examples of stops they should try to improve on.

For drivers such as Dennis Takacs, the technology on board has its benefits and drawbacks.

“Before, if you had a person that passed a school bus, you needed to know the make and model of the car, was it a male or female driver driving the car?" Takacs said.

“And then you needed to know the license plate number. How are you going to get the license number when they’re coming down the hill and they drive right by you? You’re going to have to decipher that in a mirror.”

In that regard, Takacks said having the cameras provide clear evidence of a violation is helpful.

But he also expressed concern that the multi-position switch that activates yellow and red lights for drivers could be a factor in some bad violations.

In some cases, he said, drivers can bump it and not realize it’s one step from activating red and not yellow lights.

“It's like, you go, ‘Ah, now what do I do?’" Takacs said.

"You know, because you got cars that are zipping through, and you're going, ‘How do I get that [erased]. How do I get that to somebody to say that was my fault that that came on?’

“You're trying to shut it off and then trying to get the yellows back on."

‘Traffic didn’t stop yet’

Salisbury Township recorded 350 approved stop-arm violations during last school year, Losagio said.

Nationwide, there are more than 200,000 violations on an average school day.

“I'm not looking for more violations. I'm looking for a percentage of approvals to be higher based upon good violations where … I know everyone that goes out, it's fair.”Salisbury Township Police Sgt. Bryan Losagio

Despite those numbers, he emphasized that school buses remain the safest way for children to travel — and that better awareness and enforcement can make them safer still.

“I'm not looking for more violations," he said. "I'm looking for a percentage of approvals to be higher based upon good violations where … I know everyone that goes out, it's fair.”

For bus drivers, the takeaway was simple but the issue more complex.

All agreed that a few extra seconds can prevent tragedy — and make sure every violation that is issued stands up as both fair and necessary.

But for other drivers, it was a little more nuanced.

“It’s a good question,” driver Charles Crimi II said when asked if the technology has been beneficial or there are too many factors that complicate enforcement.

“At least people are getting in trouble if they’re violating the law. But that 1-10 system where you put the ambers [red lights] on, secure the bus and put it in neutral ... I feel like those are part of four seconds, but I still add another four.

“Some kids will come up to the door and be like, ‘Can I get out?’ And you have to wait because traffic didn’t stop yet.”