EASTON, Pa. — A woman named Hannah, age 22, arrived in the Moravian settlement of Bethlehem in 1745, brought along by her enslaver.

She was the first enslaved African to come to the community, but others soon followed: Andreas in 1746, Magdalene in 1747, Corydon in 1748, Thomas in 1749.

- A recently rediscovered register lists the names of enslaved Africans who lived in Bethlehem in 1780

- Lehigh University professor Scott Gordon spoke at the Sigal Museum in Easton about his discovery

- The register likely had not been noticed since 1860

Ultimately, about 40 enslaved Africans lived in Bethlehem at one time or another. Most, like Hannah, accompanied masters seeking a spiritual haven.

Others, perhaps seen by their enslavers as showing particular spiritual promise, were sent alone.

Last Thursday — more than 275 years after those Afro-Moravians arrived in Bethlehem as slaves — Lehigh University professor Scott Gordon spoke at the Sigal Museum in Easton, telling an audience of more than two dozen about how he discovered a document to led to their long-forgotten stories.

'I kind of gasped'

Gordon said that in summer 2020, he traveled to Philadelphia, ready to search the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s archives for new revelations about how residents of the Lehigh Valley were armed in the early years of the Revolutionary War.

Gordon, who studies Moravian-era Bethlehem, said he was leafing through a volume of Colonial-era documents from Northampton County, looking for troop rolls and catalogs of material, when he found something unexpected.

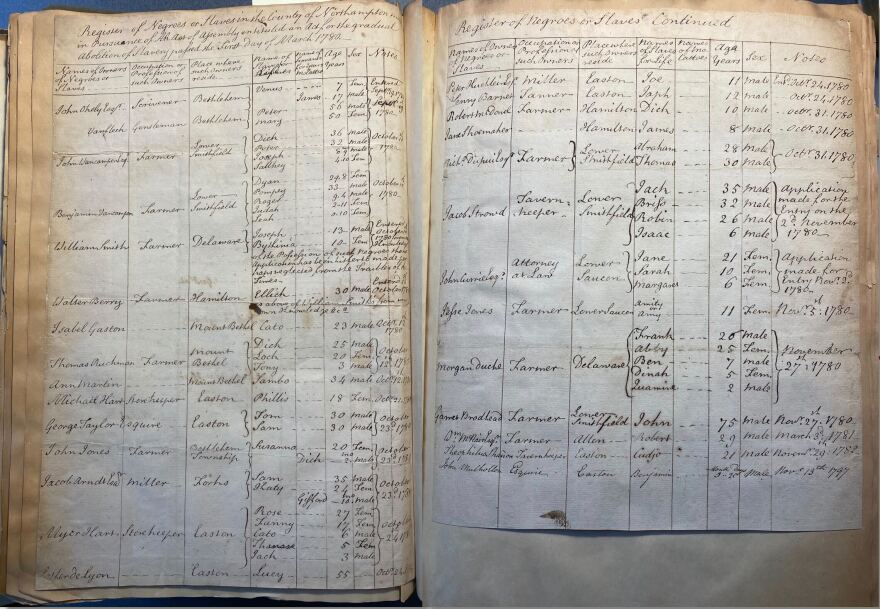

Spread over two large pages, precise script handwriting named every person enslaved in Northampton County.

The document last was seen in 1860, when historian Matthew Henry used it to compile a list of the Lehigh Valley’s slaveholders. He did not include any details about the enslaved Africans, only the number listed.

The register, and the identities of the enslaved people on it, were since presumed lost.

“I knew it was thought to be missing," Gordon said. "Otherwise, I would have simply paged past it, which everybody else who presumably used that volume did.

“I sort of gasped and took some photos, kept paging through looking for the things I was looking for, and then started texting people on the train ride home.”

A 'compromise' on slavery

The Pennsylvania General Assembly voted in March 1780 to partially end slavery in the Commonwealth. It was a sort of compromise: There could be no new slaves added, but those already held in bondage would not be freed.

To those ends, the act required someone to create a list of every enslaved African in Pennsylvania. Anyone whose name was not registered by Nov. 2 of that year was free.

Bethlehem’s enslaved population continued to grow as the deadline approached.

“For anybody who studies slavery in Bethlehem, the 1780 Northampton County Register is very surprising."Lehigh University professor Scott Gordon

By then, Hannah had been joined by her husband, Joseph — a member of the settlement bought him in 1760, reuniting the couple after 15 years apart.

When her former owner died a few years later, he willed her to the church, making it her new owner.

Enslaved Africans continued to arrive as the deadline approached: Peter and Mary, a married couple, were brought to the city in 1779; Venus, age 7, arrived in 1780.

'I've used the word 'indifferent''

“For anybody who studies slavery in Bethlehem, the 1780 Northampton County Register is very surprising," Gordon said during the presentation.

"And it's surprising because of the names of the enslaved people who are included. It's surprising because of the names that aren't included."

“Due to our love for them, we don't set them free. They are far worse off if they are set free than if we keep them with us.”A quote from a Moravian church leader regarding enslaved Afro-Moravians in Bethlehem

Moravians, fastidious record-keepers though they were, did not note the legal status of Bethlehem’s Afro-Moravians. Some of the only clues of someone’s enslavement come from documents prepared for authorities outside of the community.

In everyday life, Bethlehem’s enslaved Africans lived and worked alongside their white counterparts, involved in the same social systems. In writings, church leaders said they viewed the Afro-Moravians as no different from their white counterparts — as “free.”

“Writers trying to articulate the Moravians’ attitudes about race often resort to these sort of negative formulations, ‘unconcerned’ or ‘unimportant,’ since they're trying to capture what they see as an absence of attention or refusal to register something,” Gordon said.

“I've used the word ‘indifferent,’ which in the 18th century meant unconcerned or inattentive.”

Of course, Moravians weren’t as indifferent as to free people the church legally owned.

Gordon quoted from a letter in which one church official wrote, “Due to our love for them, we don't set them free. They are far worse off if they are set free than if we keep them with us.”

How Bethlehem’s enslaved Africans felt about life in the settlement is all but lost to history, Gordon said, but it’s hard to imagine the enslaved themselves didn’t see a difference.

“Voices of the enslaved are rarely available to us, except in what you might call distorted form,” he said. “These voices expose a gap between Moravian authorities’ indifference to matters of legal status — their belief that the lives of the enslaved were really no different than the lives of the free — and Afro-Moravians’ own perspective.”

'Imagine what she could tell us'

Gordon said he couldn't find evidence of any discussion of what to do about the partial abolition law in records of church meetings.

There also were free Africans living in Bethlehem, such as one named Magdalene, he said.

Four names from Bethlehem appear on the 1780 register: Peter, Mary, James and Venus.

“These people have never been mentioned in any discussion of slavery and Bethlehem," Gordon said. "Indeed, they were not known about. So who were these four people?”

James escaped enslavement in 1784, fleeing to Easton, then on to Philadelphia. Peter and Mary were moved to another settlement near Nazareth.

Gordon said he doesn’t know what happened to Venus, other than that she was only in the city for a short time.

Hannah, and other Afro-Moravians owned by the church, were not registered. The same indifference that characterized Moravian attitudes toward slavery, and kept them enslaved, ultimately set them free, Gordon argued.

Hannah watched her daughters, Mary and Hannah, grow up, and attended Mary’s wedding as a free woman. She was the oldest Moravian in America when she died at 92.

“Imagine what she could tell us,” Gordon said.