BETHLEHEM, Pa. — A broken leg and a broken psyche.

Amie Allanson-Dundon, St. Luke's senior network director of clinical therapy, believes they should be treated equally by the insurance coverage community.

The painful truth is, they are not required by law to do so.

Why?

“If I had the answer to that, we could all leave here right now,” Allanson-Dundon said Monday during the release of St. Luke’s recently completed triennial Community Health Needs Assessment at Nitschmann Middle School.

The survey identified a host of medical-related conditions and concerns of more than 6,000 Bethlehem residents who were surveyed.

“It all comes down to money."Wendy Lazo, president, St. Luke's Bethlehem campus

Overall, St. Luke’s surveyed more than 15,000 residents throughout its 11-county reach The results showed residents’ top three priorities: Access to care, chronic disease prevention and mental health.

“It all comes down to money,” Allanson-Dundon told the gathering. "Today, they can get away with not paying for those [mental health] services. The funding from the state and federal government isn’t there.

“And many of the payers who do pay for mental health services are running at a deficit already.”

Fifty-two percent of Bethlehem residents surveyed cited mental health as a top priority, nearly mirroring data from those surveyed in Allentown (54%) and Easton (51%).

Among students, 27% reported being bullied. Forty-seven percent reported not feeling connected to their community.

Mental health coverage

Mental health and physical health insurance coverage are not always the same, because of factors such as provider shortages, lower reimbursement rates for mental health professionals, and a historical lack of parity.

That's even though federal laws such as the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act aim to make them more equal.

Insurers often offer lower reimbursement rates to mental health providers, discouraging them from joining insurance networks and sometimes requiring more out-of-pocket payments from patients.

“But we need someone to drive that change. But no one is stepping up.”Wendy Lazo, president of St. Luke’s University Health Network’s Bethlehem campus

The solution, said Wendy Lazo, president of St. Luke's Bethlehem campus, is to reform the health care payor system, which are third-party payments from insurance companies and the government.

“But we need someone to drive that change,” she said. “But no one is stepping up.”

St. Luke’s has been at the front line of assisting those with mental health challenges, including, but not limited to, nearly 4,500 mental health visits in Bethlehem Area School District, 315 in the Northampton County adolescent admissions for treatment at St. Luke’s Adolescent Behavioral Health Unit.

St. Luke’s also has received a 100% satisfaction rate among mothers who participated in the Moving Beyond Depression Program with its Nurse Family Partnership.

'A long way to go'

Among Bethlehem students, 43% reported feeling sad or depressed.

“We’re making progress, but we still have a long way to go,” said Rosemarie Lister, St. Luke’s senior network director of community health.

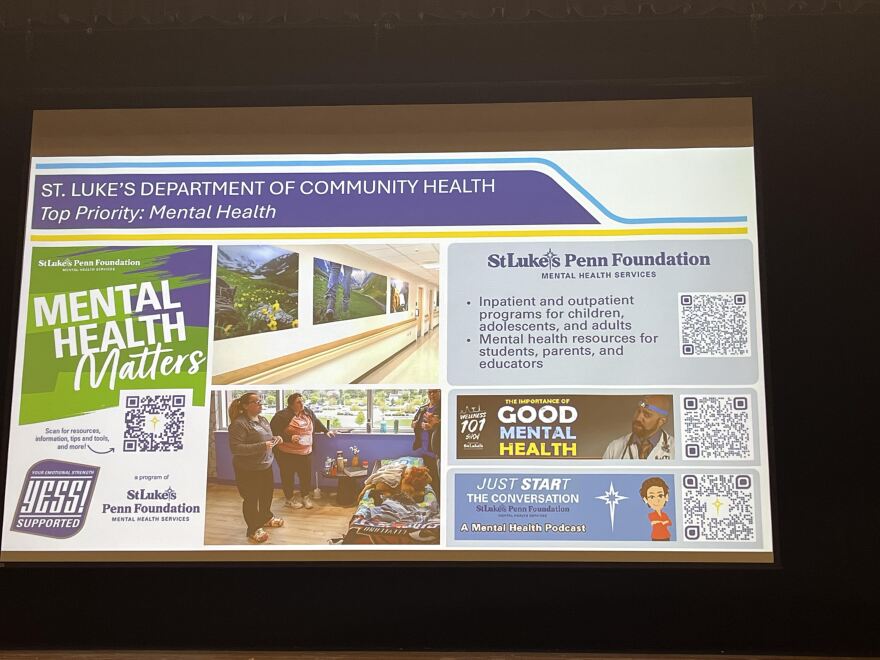

St. Luke's Penn Foundation offers inpatient and outpatient mental health and addiction programs for children, adolescents and adults, and provides information and resources for individuals, parents, educators and the community.

“Also “Yess!” is a school-based program in Bethlehem that had 4,000 encounters.

“We need family members and people in the community to know what’s going on in mental health," Lister said.

As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, nonprofit hospitals are required to conduct a CHNA every three years to maintain tax-exempt status under section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code.

Access to care, food insecurity

The two remaining areas of primary concerns of those surveyed were access to care and chronic disease prevention.

Access to care covered connection to care, workforce development and transportation and housing.

While 93% of Bethlehem respondents reported visits to the doctor, only 62% without health benefits visited their doctor.

Nearly 50% of renters reported being cost-burdened, said Rajika Reed, St. Luke’s vice president of community health.

Census.gov defines cost-burdened as spending more than 30% of one’s gross household income on housing costs such as rent, utilities and other fees.

“Food insecurity is connected to chronic disease."Rosemarie Lister, St. Luke’s senior network director of community health

Data showed 36% meet standards for ALICE, an acronym for Asset Limited Income Constrained Employed, meaning they make too much to qualify for public assistance, but are unable to afford a basic, county-specific budget for essentials like housing, food, health care and transportation.

Chronic disease prevention dealt with food insecurity, nutrition education and promotion.

About 78% reported having a chronic disease, 40% reported having high blood pressure, 32% reported having high cholesterol and 75% reported being overweight or obese.

Only 7% reported having eaten five servings of fruit and vegetables daily.

“Food insecurity is connected to chronic disease,” Lister said. “We learned that people just don’t have enough to eat. Not only that, but they don’t have enough healthy food to eat.”

St. Luke’s partners with the Rodale Institute Organic Farm, food pantries, United Way school partnerships, Meals on Wheels and Second Harvest Food Bank to address the shortfall.

St. Luke’s also sponsors an Older Adult Meals Program, which offers healthy meals to those 65 and older at a cost of $3.99.

As the event at Nitschmann wound down, a member of the audience put an exclamation point on many of the issues the survey showed needing addressing.

“What is the solution to all these issues?” asked Joseph Welsh, of the Lehigh Valley Justice Institute.

“Right now, we’re a democracy. We need to make it clear to our elected officials there are vital services being cut that we need. We need to communicate this to all of them.”