PALMER TWP., Pa. — When Mary Golden, a yoga instructor, first started practicing ten years ago, she said classes were mostly attended by women.

But now, yoga classes are starting to see a new type of student. Veterans are using yoga as a way to process the issues they deal with when they return from service. In fact, it's a practice the VA officially recommends it on its website.

At 5:30 p.m. Wednesdays, The Palmer Recovery Center becomes holds free trauma-informed yoga for, sponsored by Battle Borne, a nonprofit agency that supports Lehigh Valley Veterans.

- Trauma-informed yoga can help veterans and others dealing with anxiety do yoga in a way that feels safe

- Mary and Wayne Golden are a married couple who teach a class at the Palmer Recovery Center

- The class happens every Wednesday at 5:30 p.m.

Mary and Wayne Golden, a married couple, teach the class, along with Jennifer Mann. They alternate weekly.

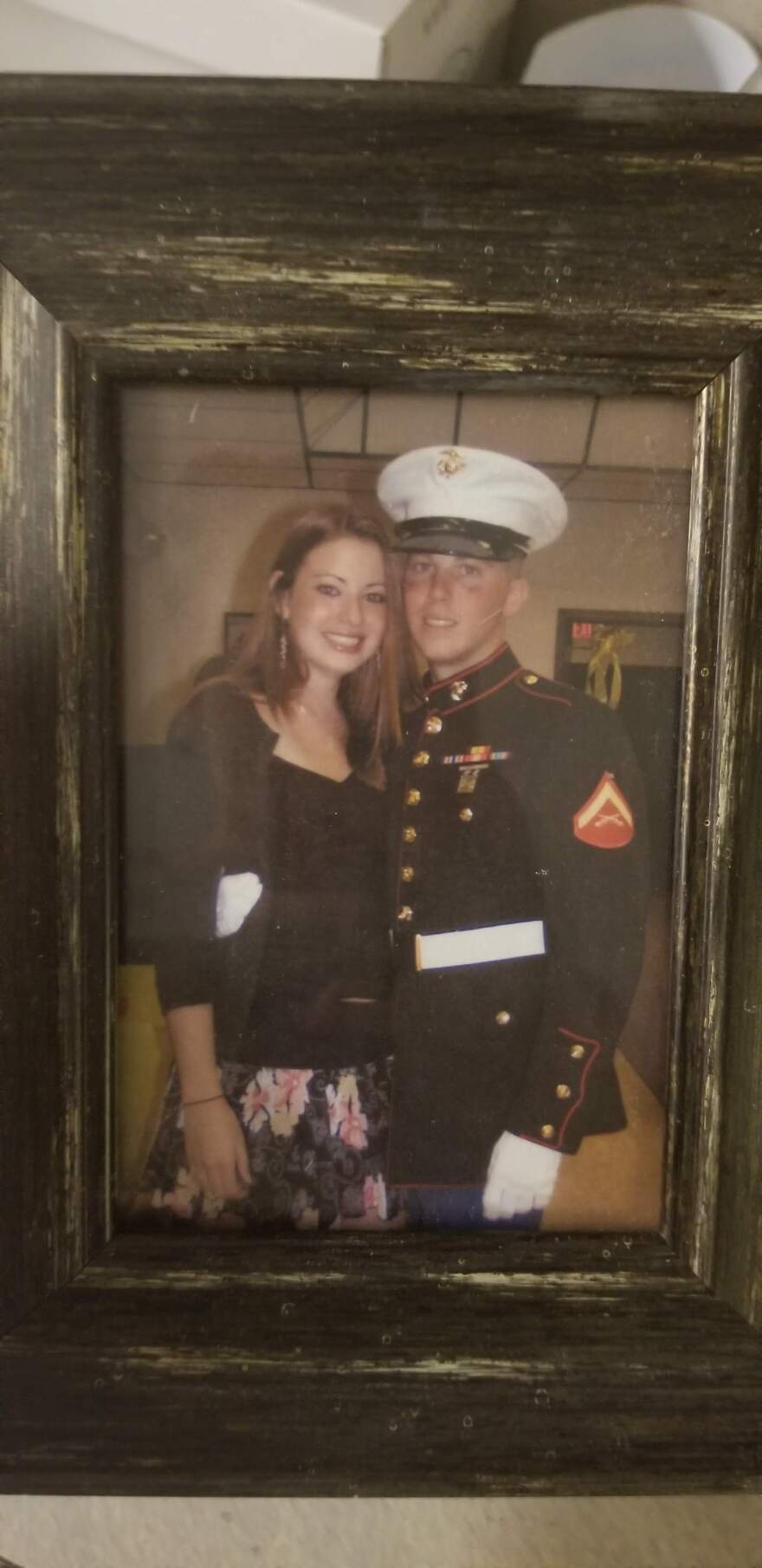

Mary has a yoga and health coaching business. Wayne teaches eighth grade social studies. He’s also a Marine who served eight years and did two tours in Iraq.

How it started

They met at 19 years old, in 2002. It was right before Wayne signed up for the Marines. They wrote letters to each other during his time in boot camp. Five years ago, they got married. They also have two children, a 2-year-old and 6-year-old.

Mary got into yoga in 2011. Soon after taking her first yoga class, she decided she wanted to be a yogi.

“I had never really learned self-care prior to that,” she said. Her parents had always been supportive, but she said she felt pressure to take care of others, sometimes at a cost to herself

“When I first tried yoga. I was like, everything else mattered,” she said. “Everyone else mattered.”

She was working three jobs, and felt like she was running in circles.

“I just didn't have that understanding and value system around, ‘Oh, what do I want? What is next for me and my time and energy?'”

For her, yoga was the answer. The physical and mental benefits were secondary to the feeling of empowerment and worthiness it gave her — that it was OK to put herself first.

When she started teaching, she’d practice her techniques on Wayne.

“You were definitely my favorite student to try things on."Mary Golden, yoga instructor

“You were definitely my favorite student to try things on,” Mary said.

“It wasn't that easy to get me on board,” said Wayne. “It took a little time. I was like, ‘Yeah, go do yoga,’” he said.

He struggled with PTSD from his military service, which gave him anxiety and trouble sleeping.

What really drew him into the practice was the spiritual aspects of yoga — the meditation, the chants of the Gayatri Mantra and ancient texts like the Bhagavad Gita.

“Mantra is a tool,” Mary said. “Having a physical practice is a tool. Understanding breathing, pranayama, is a tool.”

Once they had that toolbox, they wondered why more people don’t.

Mental health

In 2019, they partnered with The Farm in Harmony Township, N.J., to offer yoga to veterans. The couple wanted to give veterans an alternative way to address issues like PTSD, anxiety, stress and sleeplessness, “that don't always involve a pill,” Mary said, “or something that honestly could be life-threatening and destructive.”

The issue hits hard with Wayne, who’s lost more fellow service members to suicide than war.

30,177 Global War on Terror veterans have killed themselves. Only 7,057 have died in service.2021 study by the Watson Institute at Brown University

A 2021 study by the Watson Institute at Brown University found 30,177 Global War on Terror veterans have killed themselves. Only 7,057 have died in service.

Another report on suicide prevention, by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, found in 2020, almost 17 veterans committed suicide a day in the United States, though that number has been decreasing since 2006.

“I always say it's just a miracle and a blessing that he's here with me today and with us,” said Mary. “The way life has gone, it could have been really a statistical, just really bad scenario.”

Iraq

Wayne served four years of active duty. He lived on a base in North Carolina and was trained in riverine assault.

“Basically, I drove boats up and down waterways,” Wayne said. “We hop off the boats and do water to land.”

In 2004, he served two tours in Iraq. “When I was overseas, it wasn't pretty,” he said. “I'm very fortunate to be here today, considering everything.

“Ramadi, that was the most dangerous place in the world. We were just constantly on edge.”

The rules of engagement were that service members not allowed to fire unless they were fired upon.

“Basically, you're just waiting to get shot at before you can shoot somebody else,” he said. “You see a lot of stuff.”

He saw his friends get hurt, and struggle with their mental health.

“They are hurting themselves,” he said. “So they don't go out and just murder an entire village.”

His convoy was involved in several explosions, and there were firefights with insurgents.

“You go into buildings not knowing what's gonna happen."Wayne Golden, Marine and social studies teacher

“You go into buildings not knowing what's gonna happen,” he said. “You come around a corner and there’s a family.”

The violence was difficult to endure, he said, but so was the abject poverty. “The people don't have anything,” he said.

“They just don't feel anyone cares about them. And then we're there doing what we need to do for God knows what reasons.

“We're all human, right?” he asked. “I don't want to really see people suffer.”

When he returned from his second tour at the age of 23, he turned to substances — cocaine, heroin and alcohol to numb the pain, instead of processing it. A lot of it was simply to be able to sleep, he said.

He enrolled in college to study history and education, but felt isolated from younger students who hadn’t ever seen the ugliness of war.

At age 27, he decided to get clean. Mary gave him a pamphlet about a veterans retreat at the Omega Institute for Holistic Studies in Rhinebeck, New York.

At first, he was resistant to the idea of going.

“He was like, ‘Listen, the only way I'm going to a veterans retreat is if it's led by a veteran, and if it's Buddhist,'” Mary said. It was. The veteran who ran it served in Vietnam and had similar experiences with PTSD and substance abuse.

more limo

“He felt comfortable with the leader of that retreat,” Mary said, ”someone in that space of offering healing or advice or self-care methods, was an actual veteran.

“They can say, ‘I've been through that.’ And I can say, I've been close to that. And I have empathy. For us,'” she said.

Teamwork

That’s why they now teach their class together at the recovery center at 2906 William Penn Highway. They found veterans are more comfortable being part of a community where other veterans are there, leading or offering support.

Mary does the yoga, and Wayne watches the room, making sure space stays secure. He locks the doors when class starts, and unlocks them when it’s over.

One of the reasons Wayne struggled with it is the fact that yoga is not an immediate solution.

“You got to practice and deal with it, and then it becomes part of your lifestyle.”Wayne Golden, Marine and social studies teacher

“You got to practice and deal with it, and then it becomes part of your lifestyle,” Wayne said. It’s something that he and Mary have to remind each other of, in between work, coaching and raising a family.

It’s something they say can apply to anyone, not just veterans.

“Life feels overwhelming,” said Mary. “How do I get comfortable with the uncomfortable stuff, because there's going to be uncomfortable stuff if you're going to choose to be human.”

She says breathing techniques are a tool people can use when they’re dealing with stress off the mat.

“Oh, I can practice my four quarter breathing and know how to lower my heart rate and shift my nervous system from fight or flight to rest,” she said. “That's empowering.”

Community

The class is open to anyone, not just veterans. They’ve had community members attend who have gone through substance abuse issues and are dealt with challenges like self harm and divorce.

“There is this energy of mutual understanding,” said Mary. “We're here to do that self care and not judge and just be on this mat together.”

Though it can be practiced at home, in-person classes can offer a sense of connection. People are quiet at the start of class, but after, everyone will talk to each other, she said.

“That sense of community is what they really get the most out of it.”Mary Golden, yoga instructor

“That sense of community is what they really get the most out of it,” Mary said.

Veterans and others are also welcome to bring a support person or kids with them to class.

“Any age, any ability, level, any body type, everyone's welcome,” said Mary.

Trauma-informed yoga

In a trauma-informed yoga class, interruptions are minimal. People know where the doors, bathroom and water cooler are located.

For people who’ve undergone extreme trauma, the sound of a door slamming, a truck going by or a heated argument happening on the street can trigger feelings of panic.

Wayne talks people through changes happening inside and outside the room.

But it’s not just securing the space from outside dangers. They also work to create an active feeling of psychological safety inside the room. It’s a space that’s welcoming and nonjudgmental.

“We've had people, maybe they're tired, maybe they're having a rough week, maybe they're emotionally depleted,” she said, “Lie down and relax on the mat, and be around the energy … that healing space.”

If she’s guiding the class into a lunge pose, she’ll give them different options. And she always speaks in an invitational way.

“It's never giving a directive or a command."Mary Golden, yoga instructor

“It's never giving a directive or a command,” said Mary. “It's more like, you're welcome to do this.”

She says the small adjustments in language and framing are empowering, and help increase people’s sense of control in their body.

For people in general, but especially for those whose bodies hold trauma, it can be a challenge for them to know what feels good. She says stuff like, “If you want to try this, try this,” or will ask “How does that feel?” It helps build a connection between the mind and the body in an intentional way, she said.

“A lot of it is about what can we let go of, what can we leave behind here?” she asked. “Because there's so much that is embedded in that's not serving us. And that's tension. That's the pain. That's the physical and mental anguish that sticks around after trauma.”

This is especially helpful for veterans, Wayne said, who might be in great shape physically, but are unaware of the damage their body’s gone through.

Making it your own

Mary said her hope is people just walk through the door. “There's only practice, no perfect,” she said. “Once you show up for yourself, that's it.”

Wayne said yoga has helped give him a better life.

“It just gives me a moment, instead of just being so reactionary,” he said. “I think it's also made me a little bit more human.” He also said it's given him better sleep.

“Once you show up for yourself, that's it.”Mary Golden, yoga instructor

“We feel like it's like, secret code for life,” Mary said. The different parts of the practice, the meditation, the breathing, the physical poses and the devotional, spiritual aspects can be pieced together in many different ways.

“That's what I hope people do,” she said. “Take something that feels good and make your own yoga."