BETHLEHEM, Pa. — If you’ve eaten sweet corn, you’ve most likely seen the impacts of corn earworm.

“You grab your ears, and then when you get home and you start to take the husks off, you see — every once in a while — there's one that has a caterpillar in it, or it's just really gross at the tip,” Heather Grab, assistant professor of vegetable entomology at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, said.

“That is corn earworm.”

An annual pest across Pennsylvania, corn earworms can cause damage to both sweet and field corn, cutting into farmers’ profits and home-gardeners’ yields.

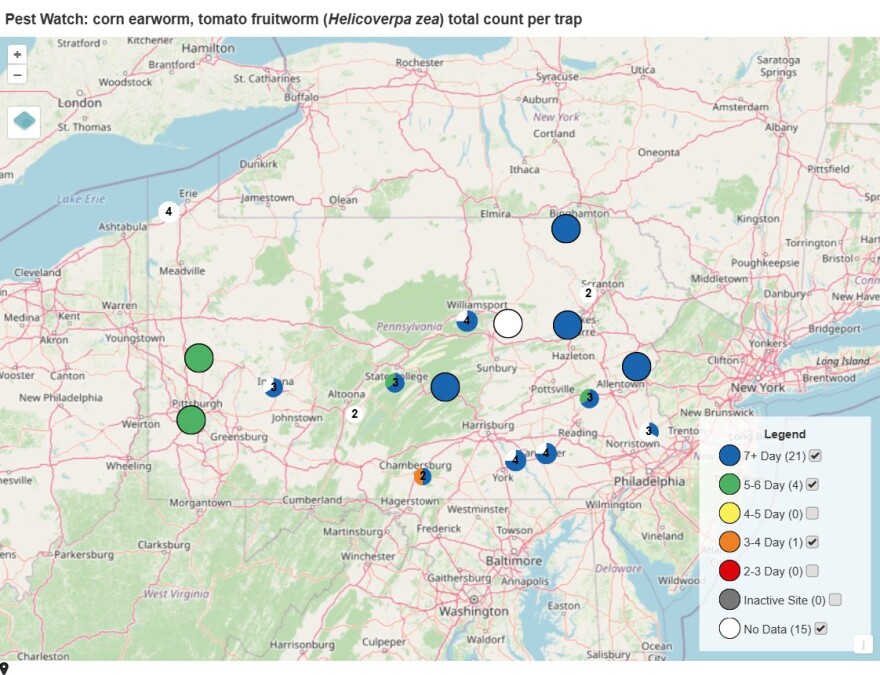

To help track populations — which, because of climate change, might be growing — Penn State this year has launched a new PestWatch webpage.

With the data updated weekly with trapping reports from across the state, growers can use it to help inform their pest management practices.

In the Lehigh Valley, corn earworms have been trapped this year in both Lehigh and Northampton counties. However, counts currently are low, categorized as “almost absent.”

One insect, several names

Corn earworms are native to the United States, with continuous population cycles in Southern states, including Texas and Florida, where corn crops are abundant.

However, every summer, the adult moths hitch a ride on storms and travel north up the coast to the commonwealth.

“Once it gets here, and the temperatures are suitable for it, then their population takes off here,” Grab said.

“And we can have maybe two, sometimes even three, generations of those pests that are produced from lay[ing] eggs in our sweet corn here.

"Those moths hatch out and produce new moths that go on to reinfest other sweet corn.”

Female moths will lay one or two eggs on each strand of corn silk. About the size of a pinhead, the eggs are similar in color to the silk.

“As soon as they hatch, those caterpillars will start to chew their way down the silk, and they'll pretty quickly find themselves inside the top of the ear,” Grab said.

“And they'll spend the rest of their life chewing through all the silks in there and eating all the top of that developing corn.”

“It does attack lots of crops, but there's, I think, nothing that a female corn earworm likes better than fresh, silking sweet corn. So, that's where we see a lot of problems happen.”Heather Grab, assistant professor of vegetable entomology at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences

After fully developing as a caterpillar, it’ll chew its way out of the ear, usually through the husk, and then “plop” onto the soil and form a pupa, she said.

“Basically, it went through its last stage of molting, and it's just going to sit there as a little brown, one-inch-long pupa in the soil until the conditions are right the next year for that moth to emerge,” she said.

Growers might know them by different names. Corn earworm also is called tomato fruitworm and cotton bollworm, depending on its diet.

“It's one insect with lots of different common names, because it's actually quite a generalist insect,” Grab said.

“It does attack lots of crops, but there's, I think, nothing that a female corn earworm likes better than fresh, silking sweet corn. So that's where we see a lot of problems happen.”

Evidence of overwintering

Historically, the commonwealth’s cold winters have killed off any overwintering corn earworms — but that’s changing, officials said.

While it’s hard to confirm exactly where a moth came from, Grab suspects moths for the past two years have been successfully overwintering in the southeast and southcentral parts of the state.

“What we're actually seeing is, because of climate change, where we're having especially these warmer winters and higher-than-average nighttime temperatures in the winter," Grab said.

"Things just aren't getting quite as cold. We actually do now see some evidence that corn earworm is overwintering in Pennsylvania.”

Because the eggs are nearly impossible to scout, Penn State has partnered with the Pennsylvania Vegetable Growers Association to fabricate and place large wire mesh traps with pheromone lures throughout the state to trap the moths.

A network of primarily Extension educators, but also growers, report data from the traps for the website.

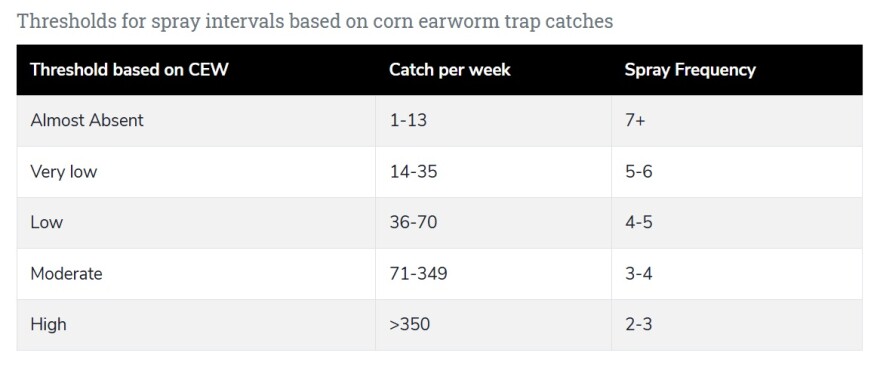

“They're going out every week, checking those traps, counting all the moths that are in them, which is sometimes a lot,” Grab said.

“They count up all of those moths so that we know what the risk level is in any given week. And then they report that into our database and, as soon as reports are made into that database, that updates live on our new website.”

Referencing trap data over the past two years, Grab said there’s “strong evidence” of corn earworms successfully overwintering last spring, she said.

“As soon as it was warm enough, there were corn earworms that were showing up in our traps,” she said.

Growers also that spring reported corn earworm damage — generally a time when crops are safe ahead of the annual migration.

“As soon as we put traps out, we saw this early peak up in populations that was probably coming from these ones that were able to successfully overwinter here.”Heather Grab, assistant professor of vegetable entomology at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, said.

“And then this year, we're seeing the same exact pattern,” Grab said.

“As soon as we put traps out, we saw this early peak up in populations that was probably coming from these ones that were able to successfully overwinter here.”

In PestWatch’s most recent update, published Wednesday, corn earworm was detected at 20 of the 21 reporting sites across the commonwealth.

Management practices

A native insect, corn earworms have natural enemies at both the moth and earlier stages.

For the former, there’s night-flying birds such as nightjars, whip-poor-wills or swifts, as well as bats.

Other insects prey on the eggs or during the early larva stage, including spotted lady beetles, minute pirate bugs and big eyed bugs.

However, commercial farmers often use insecticides, spraying crops to kill corn earworms off, also harming those natural predators.

“If there's not very many moths around, and growers haven't been spraying, they likely have really good populations of these" natural enemies, Grab said.

“All of these natural enemies love to hang out in sweet corn that hasn't been sprayed, because they love to eat the pollen, and they also love to eat all of the other little insects that tend to show up and associate with that pollen.”

A “conventional approach” would include starting sprays as soon as the crop becomes susceptible, then continuing to spray regularly throughout the season.

Growers also can choose to sow Bt corn, a type of seed genetically modified to protect corn from corn earworm, she said.

However, there are fewer varieties, and there’s still a stigma with consumers when it comes to GMO crops.

With the PestWatch data, growers can be more informed as they decide how often to spray, preventing over-spraying.

“In the past, we had kind of a static website," Grab said. "But we were working this year with the Southern IPM Center, and they've been helping us sort of manage our database.

"And also were able to produce all of these graphics and tables that update in real time as folks in our network are making reports."

The South IPM Center, or Southern Integrated Pest Management Center, is part of the U.S. Agriculture Department, and focused on a science-based approach to managing pests, according to the organization’s website.

With the program around since the 1990s, researchers are working on speeding up the data collection — from weekly to real-time, and even forecasting into the future.

A postdoctoral student working with Grab is compiling data from the commonwealth, as well as other states, to create a forecast model to help predict where corn earworms crop up.

Another student is working on automated traps that would feed data to the website in real time.

“The dream would be to be able to use cellular networks to relay that data back to our database so we could actually get something like a daily count," Grab said.

"Which would be even more helpful for growers to be able to make management decisions based off of what's happening just yesterday compared to what happened like a week ago.” Grab said.