BETHLEHEM, Pa. — While the Lehigh Valley was battling oppressive heat and humidity this week amid Fourth of July fireworks and barbecues, a new record was set for the highest average global temperature in recorded history.

And then, the next day, the record was broken again.

- The Earth's hottest average temperature was recorded Tuesday, at 62.9 degrees Fahrenheit

- Experts point to both climate change and El Niño as likely drivers

- There are ways to prevent future warming

Researchers on Monday recorded the hottest average global temperature until Tuesday, the Fourth of July, broke the record, according to the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer, which tracks and compares global temperature data from 1979 onward. The average global temperature reached 62.9 degrees Fahrenheit, surpassing the August 2016 record of 62.46 degrees.

While the Lehigh Valley is no stranger to the effects of climate change, from the rounds of hazy Canadian wildfire smoke to more frequent severe weather, the new record is a startling reminder of how global warming has local impacts, and the work needed now to prevent further warming.

"It's that our system is adapted to the current climate, and when you change it, all those adaptations have to change to keep up with the changes."Ray Martin, meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Mount Holly

“The planet's climate has varied a huge amount over a long period of record, 4 billion years,” said Ray Martin, meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Mount Holly. “And it's important to remember for us that the problem with climate change is not necessarily that we're going to destroy life, or obliterate the human race, specifically.

“It's that our system is adapted to the current climate, and when you change it, all those adaptations have to change to keep up with the changes.”

Why is it so warm?

At the end of June, Michael E. Mann, a presidential distinguished professor in the Earth and Environmental Science department at the University of Pennsylvania and a leading voice on climate change, made a prediction.

“This will almost certainly be the warmest year on record, courtesy of warming trend + large El Niño,” said Mann in the June 24 post. “So we can expect [the] warmest month, warmest week, warmest day and probably warmest hour.”

It turns out, he was right — or, at least temperatures are trending that way.

As I said before...

— Prof Michael E. Mann (@MichaelEMann) July 4, 2023

(source: https://t.co/42TAWw5NhL) https://t.co/oxXnX5jkCv pic.twitter.com/aWlf4H9wB0

A little over a week after Mann sent the tweet, researchers recorded the world's hottest day on record.

Scientists have attributed the temperature increase to a combination of El Niño and climate change. The former is a climate pattern that occurs when trade winds weaken and warm water is pushed back east, toward the west coast of the Americas.

“The warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream to move south of its neutral position,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “With this shift, areas in the northern U.S. and Canada are dryer and warmer than usual. But in the U.S. Gulf Coast and Southeast, these periods are wetter than usual and have increased flooding.”

The past nine years have been the warmest years since modern record keeping began in 1880, according to NASA.

“The reason for the warming trend is that human activities continue to pump enormous amounts of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, and the long-term planetary impacts will also continue,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of GISS, NASA's leading center for climate modeling.

Couple El Niño with an already warming global climate, and the record was broken by less than half of a degree.

But an incremental increase can cause big changes, Martin said.

“A few degrees rise in temperature might result in a much more severe drought in the summer causing crop failures or you might get different rainfall patterns, which may flood some areas and drought some other areas,” he said. “Certain natural species which need snow, they're not going to see as much snow or cold weather — they might have to migrate north. Other species will migrate north toward us from areas that we don't see them currently.

“It's a matter of adapting to the changes that are going to happen, because we changed the climate.”

More heat, more flooding, more pests

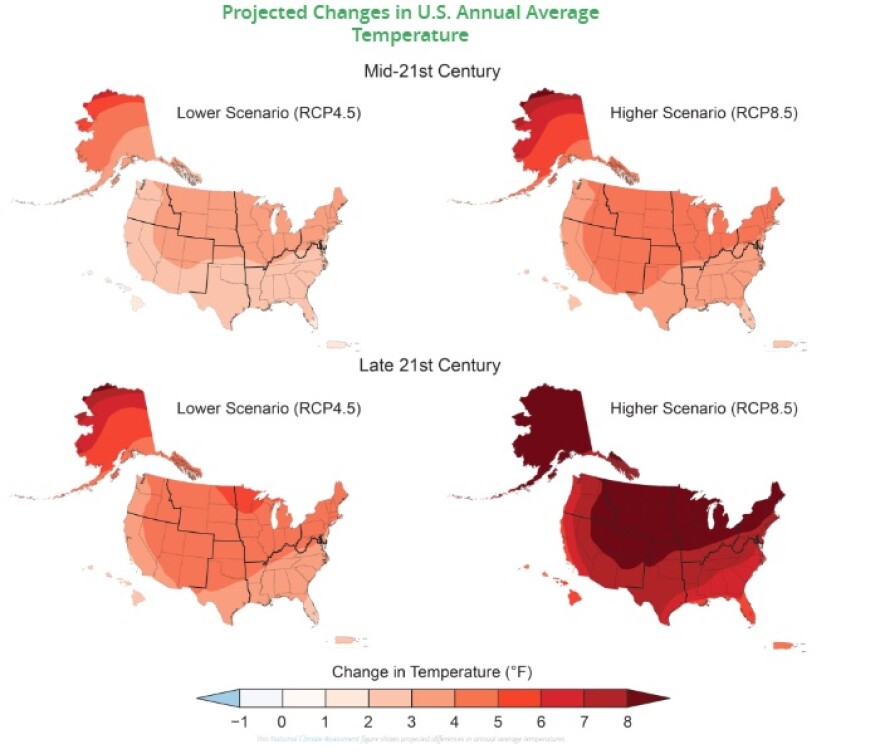

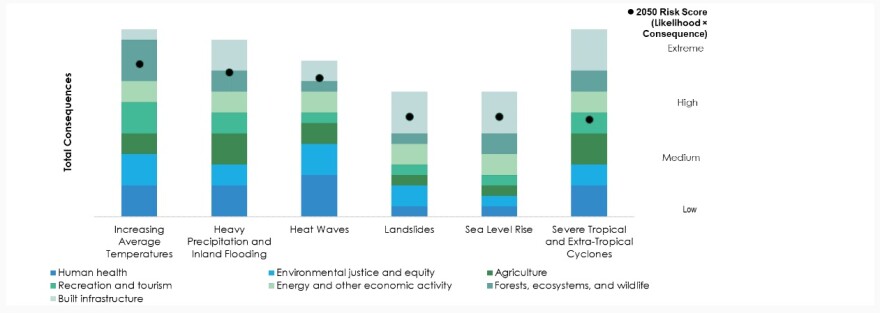

Climate change is expected to bring more heat and flooding to the commonwealth, as well as increased pests and disruptions to agriculture, according to the state Department of Environmental Protection. Over the last 100 years, the state’s average temperature has increased by 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, and is expected to warm another 5.9 degrees by 2050.

“While rare historically (less than once per year, on average), days above 95 degrees Fahrenheit are projected to occur about 12 times per year by mid-century and 31 times per year by end-of-century,” according to the DEP 2021 Climate Change Impacts Assessment. “The warmest parts of the state could experience up to 37 days above 95 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050.”

Hotter summers and milder winters can cause increased prevalence of mosquitos and ticks, as well as the illnesses they can transmit, West Nile and Lyme disease, respectively.

Pennsylvania already has some of the highest numbers of cases of Lyme disease in the nation, with nearly 12,000 in 2017 – triple the number from just ten years ago. This increase is possibly due to the western expansion of Lyme-bearing ticks and warmer winters that are leading to higher tick populations.

Researchers have called Pennsylvania “ground zero” for Lyme disease. For more than a decade, the commonwealth has ranked in the top 10 states with the most cases of Lyme per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2021, it was third in the nation, with 2,900 cases reported.

Reached by email Friday, Mann said Pennsylvania and the Valley can expect “more of what we’re already seeing” as climate change worsens.

“More extreme and deadly heat, worse droughts, wildfires and the smoke that comes with them, and worse flooding (because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture so when it rains you get more of it),” he said. “We just published a study the other day showing that the East Coast is a hot spot for extreme ‘compound’ heat/drought events — that’s simultaneous heat and drought, the sorts of conditions that produce those wildfires we’ve seen back east this summer (mostly in Canada but the wind patterns bring them down to us).”

The study, “Three things to know: Climate change’s impact on extreme weather events,” included a worst-case scenario: “by the late 21st century approximately 20% of global land areas are expected to witness approximately two [compound drought and heat wave] events per year. These events could last for around 25 days and a fourfold increase in severity.”

‘It’s not either/or — it’s both’

The record-breaking global temperature provides another reason to take action, said Carolynn Van Dyke, of the Lehigh Valley chapter of Citizens’ Climate Lobby, a nonprofit environmental group.

“At present, we’re focused particularly on two initiatives of the national CCL organization, Healthy Forests and Clean Electrification,” Van Dyke said. “By protecting, expanding and managing our forests in a way that is climate-smart, we can pull the equivalent of 22% of America's carbon pollution by 2030. During hot weather, trees can reduce temperatures by 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Electrification will make us healthier by cleaning the air we breathe in our homes. That’s particularly important when smoky air (and heat) keep us indoors.”

The group is also focused on reintroducing and supporting the federal Carbon Fee and Dividend Act, which proposes a carbon tax on fossil fuel companies that is given as a dividend, or “carbon cash back” payment, to Americans.

In addition to large-scale legislative changes, residents can also help prevent further warming at home.

Using renewable energy, weatherizing homes, investing in energy-efficient appliances and reducing water waste are just some of the ways residents can help, according to the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council.

“It is important to realize that we may have the power to fix that, reduce CO2 emissions, but there is, of course, a natural climate change cycle as well,” Martin said. “We don't want to cause our own harm, in other words, by altering the climate unnecessarily.”

Asked if society is past the point of proactive work and must instead learn to adapt, Mann said a combination of tactics is needed.

“We must prevent whatever warming we can, while adapting to those impacts that are now inevitable,” Mann said. “So it’s not either/or — it’s both.”