BETHLEHEM TWP., Pa. — Walking the trails at St. Luke’s Arboretum, it’s hard to miss the new addition — a bird house at the top of a 15-foot pole, made up of a dozen individual white gourds.

Earmarked for purple martins, a migratory species threatened due to pesticides, habitat loss and collisions, it already has more than a few residents.

“We put it up in November, just so it'd be ready for the spring, because I didn't know exactly when they would come,” said Tom Fiorini, St. Luke’s director of landscape services.

In June, purple martins started to arrive — first only a few, before chicks came along, adding to the population.

“We thought it was a little late, because when you read about it, they're supposed to come in April — it was kind of a surprise,” Fiorini said. “I didn’t expect [them], but I was hoping.”

Expert flyers with a voracious appetite

Purple martins are known as long-distance migrants, spending winters in the Amazon Basin in South America and returning north in spring.

Adult males look almost iridescent from their dark blue-purple feathers. While the females have some similar coloring, they have more gray and brown feathers.

They are expert flyers, known to “eat, drink and even bathe on the wing,” feeding on airborne insects, according to the American Bird Conservancy.

“They go wild — 600 to 2,000 insects a day, each one,” Fiorini said.

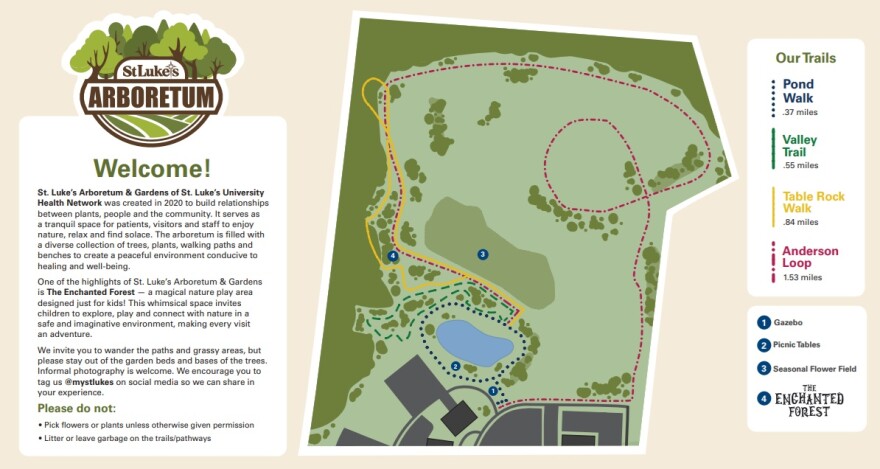

Their appetite is a huge help at the arboretum, on the St. Luke's Anderson Campus, 1872 St. Luke's Blvd., which boasts 75 acres of flowers and four trails.

“It also helps the bees and butterflies, because it kind of balances out the environment for them,” said arboretum intern Jocelyn Valentin. “Which helps the bees pollinate more of the flowers around us.”

Describing them as fun and interesting birds with a flair for acrobatics, Fiorini said they’re also fast, topping out at speeds of 40 mph.

“They can go between 1,000 [and] 1,300 feet,” Valentin said. “And compare that to, like another kind of bird, they only go to 500, so they fly pretty high.”

However, unlike many other native species of birds, purple martins thrive in close proximity to humans. In the Northeast, like the Lehigh Valley, they’re dependent on man-made bird houses, often shaped like gourds.

“They used to take cavities of trees or woodpecker holes and use those, but now they don't depend on them as much anymore,” Fiorini said.

“And I guess they're more susceptible to predators, too, in their natural setting. When you put these houses up, I guess they prefer to be by people. They're just a little safer from the predators, things like that.”

And, once they find a home, purple martins “exhibit a very high level of site fidelity,” according to the conservancy, returning year after year.

While listed as “least concern” under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the conservancy notes purple martins are decreasing in numbers.

Habitat loss has been a key driver of decline in purple martins, alongside pesticide use and collisions, according to the conservancy.

“The practice of removing dead trees in many forests has eliminated natural cavities used by the martin,” according to the conservancy’s website. “That, along with the competition from the introduced starlings and sparrows, has further reduced the availability of naturally occurring cavities.”

“Purple martins are vulnerable to unseasonably cold or wet weather. A sudden cold snap lasting more than three or four days can decimate flying insect numbers, starving the birds to death.”

‘Phenomenally important’

When the weather started to turn warmer this spring, Fiorini and Valentin would stop by each day, hoping for a sign that purple martins had been lured back.

Then, one June day, an app on Valentin’s phone picked up a purple martin bird call, Fiorini said. Luckily, a photographer was on-site for another event, but ran over to snap a few pictures.

Officials sent those pictures to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, N.Y., as well as to Peter Saenger of Muhlenberg College’s Acopian Center for Ornithology — both concluded they were, in fact, purple martins

“To have first year success, means you have a very good location. So, what you have done there is phenomenally important.”Peter Saenger, Muhlenberg College’s Acopian Center for Ornithology

“To have first year success, means you have a very good location,” Saenger said in a news release. “So, what you have done there is phenomenally important.”

Fiorini credited Richard A. Anderson, president and CEO of St. Luke’s University Health Network, as well as Edward “Ed” Nawrocki, president of East Region and St. Luke’s Anderson Campus, with the success of the project, as well as the ongoing work to improve and expand the arboretum.

The campus, which is named after Anderson, added the arboretum in 2020, one of the strategies to make the hospital a community destination.

“A destination campus is a place to go to the hospital, not because you're sick, but because they want to promote wellness and get people outside and be healthy,” Fiorini said.

In addition to the new bird house, trails and fields of flowers, the campus also boasts an Enchanted Forest and an organic farm, the latter managed by Rodale Institute.

To find out more about the arboretum and gardens, go to St. Luke’s website.