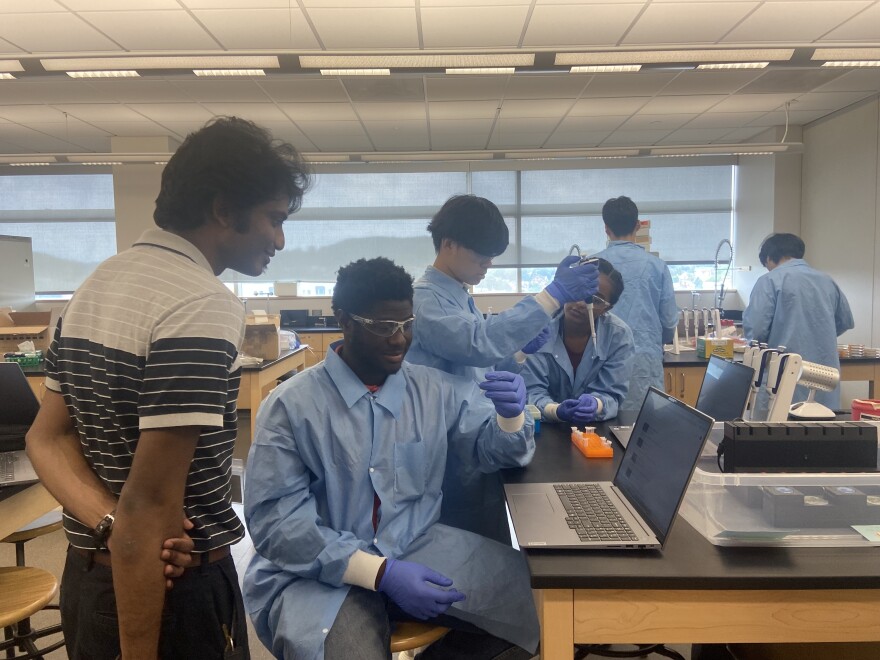

BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Three dozen students on Thursday entered a Lehigh University lab — trading their backpacks for blue lab coats before settling in at tables, organizing their laptops and readying their micropipettes.

They weren’t college students aiming to get extra work done over the summer break. They were soon-to-be-scientists — rising high school seniors from across the United States and other countries, studying bacterial genomics.

Over the past several weeks, Lehigh has hosted SSP’s International’s Summer Science Program.

It's a rigorous course involving classroom lectures and lab work, in which students get hands-on experience completing college-level research while getting a feel for campus life, preparing them for higher education.

"We want them to appreciate the diversity of people who belong in science, and we want them to appreciate the importance of working within a team that has people of all of these different types of backgrounds."Noel Mano, academic director

“We try to get a broad representation of students here, and that's across many different levels,” Academic Director Noel Mano said.

Those chosen for the program came from both high and low incomes, as well as some who will be the first generation to go to college and students whose parents have earned advanced degrees.

The program also draws from rural and urban districts and across ethnic backgrounds.

“And so the purpose, of course, is that we would like the students who have not had these academic opportunities to get that here at the program," Mano said.

"And then for the students who have been at very well-resourced schools, or from very well-resourced backgrounds, we want them to appreciate the diversity of people who belong in science.

"And we want them to appreciate the importance of working within a team that has people of all of these different types of backgrounds.”

‘Doing real science’

Ruth Tsegaye, a 17-year-old from Portland, Oregon, said she knew about the program after her brother and a friend previously participated.

After deciding she wanted to pursue a career in STEM — or science, technology, engineering and mathematics — but seeing a lack of resources at home, she applied to the program.

“I really loved the immersive aspect — the whole five weeks you're concentrated on a research task," Tscgaye said. "And it's not just learning about science, but I'm doing science, like actual research.

“And that hands-on aspect felt really compelling to me. And overall I was just really curious. I wanted to delve into a new area of biology, so I chose bacterial genomics for that reason, and I've been really loving it so far.”

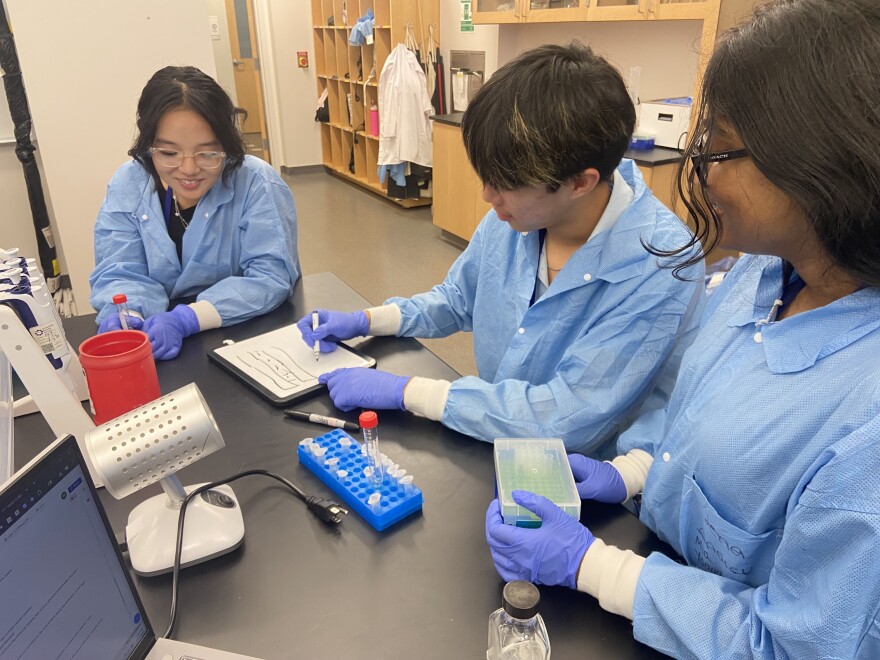

During the program, working in groups of three, students studied antibiotic resistance.

“Many bacterial populations have acquired resistance to antibiotics, and because the pace of antibiotic discovery is slowing, this is potentially a big public health problem,” Mano said.

“And not just for humans, but also because agriculture depends on antibiotics for raising animals for food, and so potentially, lots of different sectors are affected as, one by one, antibiotics become increasingly less useful.

“And so, there's a goal to understand it on many fronts, and this project is trying to understand the process of evolution by which bacteria go from being nonresistant to becoming resistant.”

Students use samples of a bacteria closely related to the cholera bacteria, but harmless, he said.

“They start out with a bacteria that has no resistance at all, and they apply a little bit of antibiotic, and the bacteria start to die, but they don't apply enough to fully kill it, and so that bacteria mostly die off, but enough survive and evolve resistance," Mano said.

“And proceeding in that fashion by applying more and backing off, bacteria die and recover. It just sort of over-cycles, until, by the end of the project, they have a bacteria that can survive several 100 times the initial concentration that would have killed them.”

As the bacterial population evolves, students extract the genomic DNA and send it to a lab for sequencing.

“Then we use the sequencing data, and we have the participants essentially mine that data, which is what they're doing now — they're in the phase of the project where they're mining that data to look for mutations that confer resistance,” he said.

“It's a process of doing real science, basically, that tries to get them comfortable with the idea of sort of sitting in that space of we know some things, but we don't know others, and I'm on that threshold where I might discover something."Noel Mano, academic director

“So we know that the populations have evolved some level of resistance, and the participants are looking in the genomic sequences for the mutations that have caused the bacteria to be resistant to the antibiotic.”

It’s junior- or senior-level undergraduate work, he said.

“There's a lot of unknowns,” Mano said. “It's a process of doing real science, basically, that tries to get them comfortable with the idea of sort of sitting in that space of we know some things, but we don't know others, and I'm on that threshold where I might discover something.”

During the last week of the program, students create and present a scientific poster, as well as a paper, outlining their findings.

“By the end, they have completed a project through all the different phases, multiple levels of microbiology and molecular biology, including genomics analysis or computational biology,” Mano said.

“And so, they've integrated lots of different skills to basically perform a project from zero all the way up to some kind of concrete output.”

‘Really get to know each other’

The five-hour flight across the United States to get to campus was the first time Tscgaye traveled via plane by herself.

“Being from the West Coast ... or been away from home for so long, I was a little bit worried about how I would adjust,” she said. “But I was surprised to see how quickly I adapted, to be honest.

“The community here is really great, and I've made a couple good friends and really quickly gotten close to my roommate.”

Similarly, Aiden Wen said the faculty and staff have created a “supportive, welcoming community” on campus.

“I really appreciate the faculty for trying to push that,” Wen, 17, of Austin, Texas, said. “They do things to try to get us in new groups, and I think the ultimate goal is just getting all 36 of us to really get to know each other.

“And the intention is to just put people together, and naturally we form friendships and connections regardless of where we come from. I think that's a really great part.”

During the program, students stay at Taylor House, a first-year residence hall, Site Director Neil Maredia said.

“We want to give that college feel as well, and give them the opportunity to be like, ‘Hey, if you plan on moving away from home, this is how life's going to be,’” Maredia said.

“You need to work on rooming with a random person, right? Getting to know them, know what their boundaries are, know what your own boundaries are, because they don't know what that is.”

Between lectures and lab work, students get to explore the region. They went bowling at Steel City Bowl and Brews,1770 Stefko Blvd., as well as visited the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Lost River Caverns in Hellertown.

Asked what he thought of the Valley, Wen said, it’s “a pretty cool area.”

“If you ask anyone here, the number one thing they're gonna tell you is the hills,” Wen said.

“I was talking to the dining hall staff one day, and they were saying they've lived here for 10 years, and the hills — they’re still not used to it.

"But it's great. I see a lot of trees — super green, actually, compared to what I'm used to.”

“That's a hard adjustment for many of them, but, by the end of the program, many of them do make that adjustment, and that's really rewarding to see — on top of all the technical skills and science they learned.”

As the program progresses, Mano said, he can see the change in students academically, especially when it comes to willingness to collaborate.

“The students who come here because of their instincts and their abilities and their interests are often the sorts of students who, in their normal kind of schooling life, find themselves leading projects, being the person in group work who is basically like marshaling the whole thing,” he said.

“The big change that we see academically is that they become comfortable as collaborators, working jointly with people to execute a project, rather than being the one person who kind of directs everything.

“That's a hard adjustment for many of them, but, by the end of the program, many of them do make that adjustment, and that's really rewarding to see — on top of all the technical skills and science they learned.”