EASTON, Pa. — Walking through the towering front gates of Easton Cemetery and along the paved path, it’s easy to focus on the graves.

It's a mixture of obelisks towering toward the sky, mid-sized sculptures and short, squat stones almost flush against the ground.

In a place so still, movement — from cars, walkers and other visitors — sticks out, signaling the property still is very much alive.

The 176-year-old cemetery is going through a realignment as death care trends change and residents favor cremation over traditional burial.

“We're still open for business. We're an active burial ground with lots and lots of room left … and we are changing our business model to diversify our revenue streams."Sharon Ashton, treasurer of the Easton Cemetery Board of Directors

At the largest green space in the city, situated in the West Ward, officials are working to generate revenue through membership, fundraisers and events.

Because, although deeply rooted in tradition and often religion, death care is an industry — and in order to thrive far into the future, cemeteries need to generate money.

“What we've undertaken is a redefinition of the cemetery,” Sharon Ashton, treasurer of the Easton Cemetery Board of Directors, said.

“We're still open for business. We're an active burial ground with lots and lots of room left … and we are changing our business model to diversify our revenue streams.

“So we're adapting the cemetery model.”

‘Things are changing’

It’s not a problem unique to the city.

Cemeteries across the United States are struggling with revenue as trends change. Burials, the more expensive option for end-of-life arrangements, are falling in popularity as cremations rise.

Last year, the cremation rate was projected to be nearly 62%, with burials at 33%, according to the National Funeral Director’s Association’s “2024 Cremation & Burial Report,” the most recent report available.

By 2045, the cremation rate is expected to reach 82%.

Across the country, the median cost of a funeral, with a viewing and burial, in 2023 was $8,300, according to the NFDA. For a funeral with cremation, it was $6,280.

“The entire industry is changing."Harry C. Neel, president and CEO of Jefferson Memorial

“The entire industry is changing,” Harry C. Neel, chief executive officer of Jefferson Memorial, a family-owned cemetery, funeral home and crematory in Pittsburgh, said.

“When they talk about death and taxes, and they think that funeral homes are forever — funeral homes are affected by trends in the nation, without a doubt.

"Two decades ago, cremation was what, 1 or 2 percent? Now, it's 40 percent in Pittsburgh, 60 percent almost in York and Lancaster, and 70 [percent] or more in Philadelphia.

"Things are changing.”

In order for funeral homes and cemeteries to stay open, there needs to be cash flow, Neel said. More so in a cemetery, “because you have all this grass to cut.”

When a cremation is chosen over a burial, that cash flow decreases — anywhere from 50% to 75%, he said.

“In a cemetery, you can sell a grave, the funeral director might sell the vault, and you can sell a marker and a grave opening,” he said.

“Well, if you have a cremation, depending on where they put it, you may just have a small grave and a grave opening.

“Some people don't even mark them, and even then, the markers are much smaller and [there's] less cash flow.

"So those that do cremate someone and bury them or put them in a niche or in a mausoleum or some other receptacle, your cash flow is still at least 50 percent less than it would have been if they'd been in a casket, and sometimes even more so.”

Cemeteries often feel such impacts more because of the constant maintenance and upkeep required.

“Nobody ever thinks about the infrastructure. We have this entire little city we have to maintain here.”Harry C. Neel, president and CEO of Jefferson Memorial

At Jefferson Memorial, which was established nearly a century ago, there are 180 acres of grass to cut and 75 members of staff to pay.

“Nobody ever thinks about the infrastructure,” Neel said. “We have this entire little city we have to maintain here.”

‘Like a history book’

Opened in 1849, Historic Easton Cemetery was created as a garden cemetery — a landscaped park that served as city greenspace.

“It was a dirt road to get here, and people came in their horse and buggy,” Kay Wolff, a member of the Friends of Historic Easton Cemetery Board of Directors, said.

“And on Sundays, it was so popular, you had to get a ticket, and the gatekeeper would only let a certain number of horses in at a time to not cause any problems.

"And people would dress up in their finery and bring their picnic baskets, and they tend to graves and talk to their loved ones.”

Wolff’s been involved with the cemetery for many years. She's created and given tours of the grounds for both adults and area students.

Her husband, Marshall, is the president of the cemetery’s board of directors. His ancestor was superintendent of the cemetery back in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“It's like a history book, looking at the gravestones and learning about the history and learning about the people that are there."Kay Wolff, a member of the Friends of Historic Easton Cemetery Board of Directors

“It's like a history book, looking at the gravestones and learning about the history and learning about the people that are there,” Wolff said.

“We have a signer of the Declaration of Independence. We had people here that fought in the Revolutionary War and the Civil War and all of these things happened around here.

"So that got me hooked on sharing the history with people and learning more about it.”

Before the cemetery was established, there were small family plots and churchyard cemeteries throughout the city.

It was Traill Green, a doctor, scientist and professor at Lafayette College, who pushed for a new, central cemetery.

“That man is my hero, because I think he did everything,” Wolff said. “He was a doctor, and he recognized the need for more sanitary burials and more controlled burials, but he was involved in just about everything around here.”

He was the first president of the cemetery’s board of directors, serving for 40 years. In 1911, a bronze statue of him was placed near the entrance of the cemetery, where it still stands.

Some of those smaller cemeteries still exist, but others were closed, the graves moved, after the cemetery was up and running.

That's how George Taylor, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, ended up at the cemetery, Wolff said.

“Of course, he died before our cemetery opened, but he was originally buried across the street from the Parsons-Taylor house," she said.

"And when that land was sold to the Easton schools to build Taylor Elementary, all of those bodies were moved up to Easton Cemetery."

Taylor’s grave, topped with a large monument, is currently under construction after an anonymous donor paid to restore his monument ahead of next year — the 250th anniversary of American independence.

Other notable residents include: George Oliver Barclay, the inventor of the football helmet; James Henry Coffin, a Lafayette professor who developed the field of meteorology; and Belle Mingle Archer, the most photographed stage actress in the 1890s, among others.

Around 1913, roads were paved throughout the cemetery grounds, totaling 8 or 9 miles, allowing cars to drive through.

The cemetery in 1990 was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

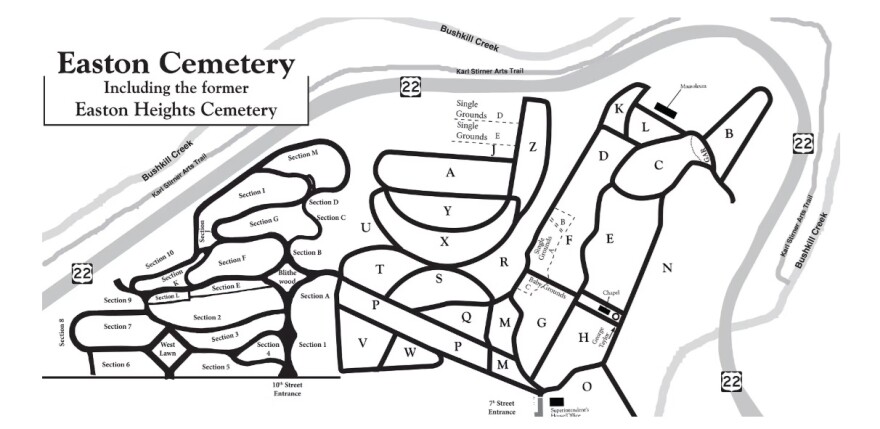

In 2020, the cemetery merged with Easton Heights Cemetery to improve efficiency, joined under the name Easton Cemetery.

In the years since, they’ve added four new board members, as well as established the Friends of Historic Easton Cemetery, a nonprofit focused on preservation and promotion.

Amy Wolff, president of the nonprofit’s board, and daughter to Kay, said, “We're not short of ideas, we're just short of people.”

“I wish we had more bandwidth and just more people to do the work to create fundraising events and programs,” she said.

“On one hand, I just want more free events, so people that live in the neighborhood feel welcome here.

“But then, we also need to raise money. I wish there was just more support to be able to do both, to have community events that are free and welcoming.

"And then just more kind of regular funding coming in to support what we need to operate and what we need to do outreach.”

The grounds extend for almost 90 acres — the city’s largest uninterrupted greenspace — and there are more than 42,000 permanent residents.

“It's come a long way, but we have so much further to go,” Ashton said.

‘A trove of opportunity’

Currently, the cemetery has two full-time workers and a few part-time employees, in order to keep costs down. The rest of the work is volunteer.

“From a horticultural perspective, garden cemeteries like Easton Cemetery are like a trove of opportunity,” Ashton said.

She said they’re working on becoming an arboretum, as well as adding rain gardens to help with storm water runoff.

“We have our grave gardening program, which is extremely important to the cemetery, because it makes the cemetery look amazing, and we have a ton of people involved," Ashton said.

"We have over 30 volunteers that show up every year, and they adopt a grave and they garden.”

Susan Albert is one of the volunteers who supports the grave gardener program.

After she and some friends went on a self-guided tour several years ago, she was “really intrigued by the history and just the beauty of the cemetery itself,” she said.

While working on certification through Penn State’s Master Gardener program in April 2022, she completed some of her required volunteer hours at the cemetery and “it just took off from there,” she said.

One of the main tasks of a grave gardener is to help plant and maintain the French graves, of which there are about 50, Albert said.

Also called cradle graves, they’re a type of grave that includes a planter box extended from the gravestone, popularized during the Victorian era.

There are several covered in overgrowth, or in disrepair, she said.

Another volunteer, a military historian, has single-handedly documented the almost 6,000 graves belonging to veterans, Amy Wolff said.

He worked with veterans’ agencies and families, making sure markers are in the correct spots and adding American flags.

“There's a lot of those kinds of people that are just quietly helping,” she said.

While the grave gardeners help with aesthetics, and there’s a training program available for those interested in gravestone cleaning, there are larger maintenance concerns, too, such as monitoring tree health and removing invasive plants.

“A lot of the trees are aging out, and some of them are in decay,” Albert said. “Some of them are damaged from storms or just from old age, so they need to be maintained for the safety of the people who walk through the cemetery, who visit their loved ones.

“And, with that in mind, the ones that have been removed need to be replaced to maintain that healthy biodiversity.”

Cemetery officials also have launched events, and opened the space for other organizations, too.

“It's just a space that we want to open,” Ashton said. “Now, that being said, it is still an active cemetery with people who are openly grieving at times, so we always have to respect that.

“We're moving toward opening up the space and inviting the public in to enjoy it more with the little asterisk that, ‘Hey, it is still a place of reverence.’”

This summer, the city held a free Sustainability Movie Night at the cemetery, aimed at engaging residents in conservation efforts.

Other events include the informal tours through Weekend Wanderers, silent book club meetings and the Green Traill 5K, set for May.

However, there has been some pushback, with some plot owners arguing it’s inappropriate to hold events in the cemetery.

“It's like a balance of having events here to fundraise and raise awareness while not upsetting anybody,” Amy Wolff said.

It’s something with which Neel has dealt, too — Jefferson Memorial holds a car show each year.

Asked about pushback he’s received, he said he’s had “a very little bit, yes, but it's pretty minor.”

He described an incident in which a decedent’s family complained on social media.

“They thought, ‘How disrespectful?” Neel said. “Well, I'll tell you, what's really disrespectful is when I run out of money and I can't cut the grass and the cemetery just turns into a junkyard.

“That's what's disrespectful.”

‘Still open for business’

For the cemetery to last long-term, it needs bodies — both in the ground and above it.

“In order to survive, you have to make revenue that far exceeds your expenses, and you have to have a product people purchase,” Ashton said.

“And if you don't adapt to the changing market conditions, you will not succeed.”

Like any other industry, the market determines what death care services are offered — and new ones are cropping up.

The cemetery already has added a scatter garden — a place for survivors to spread their loved one’s ashes, with native plants.

But officials also are interested in green burials — during which the decedent decomposes naturally without embalming, Ashton said.

And neighboring New Jersey recently became the 14th state in the country to legalize natural organic reduction, often called human composting, creating another end-of-life planning option.

“As a board member, this is my personal opinion, I would be open to looking into any form of service that meets the public's demand,” Ashton said.

“So if folks show interest in composting, and the business model shows that it would make sense for the cemetery to offer it, and we can get a license to do it, I think we'd seriously consider it along with green burial.”

Asked about traditional burials, Ashton said, “there’s plenty of room.”

But the need for volunteers, especially with niche skills, is ongoing.

“One of the biggest things we could use is people with talent that have time that would like to dedicate their expertise,” Ashton said.

“Whether you're a lawyer or you run a landscaping firm, or you're a historian or somebody who has a talent and capacity to help out.”

The cemetery struggles to keep its next-of-kin database updated, a key source of donations.

There also are efforts under way to map the cemetery, which would both allow prospective residents the ability to see what’s available digitally, as well as family members or researchers to find a grave they are searching for.

Amid all the challenges, Ashton remains optimistic.

“We are definitely holding our own,” she said. “We'll fix some things up once we're stabilized, and then we'll head into a phase of growth.

“And I'm excited for that.”

For more information, or to sign up to volunteer, go to the cemetery's website.