BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Searching a forest canopy for spongy moth egg masses takes practice and keen eyesight, John Nissen said.

“You have to have a good pair of binoculars,” said Nissen, a service forester with the state Bureau of Forestry. “And you're looking up into the canopy of the tree for an egg mass that looks newly developed and they're usually on the underneath of a branch — they're very hard to see.

“They’re like the size of a dime and you're trying to find them 60, 80 feet up and they look like dry mud on the bark. It's very challenging, to say the least.”

With spring still weeks away, state forest officials are gearing up for this year’s spongy moth hatch and urging property owners to survey their land and prepare treatment options if needed.

The invasive insect is known for a voracious appetite that can defoliate millions of acres of forest. While populations have been high in patches of the commonwealth over the past three years, the Lehigh Valley has been mostly spared.

However, experts said it’s a matter of when — not if — the spongy moths return to the region.

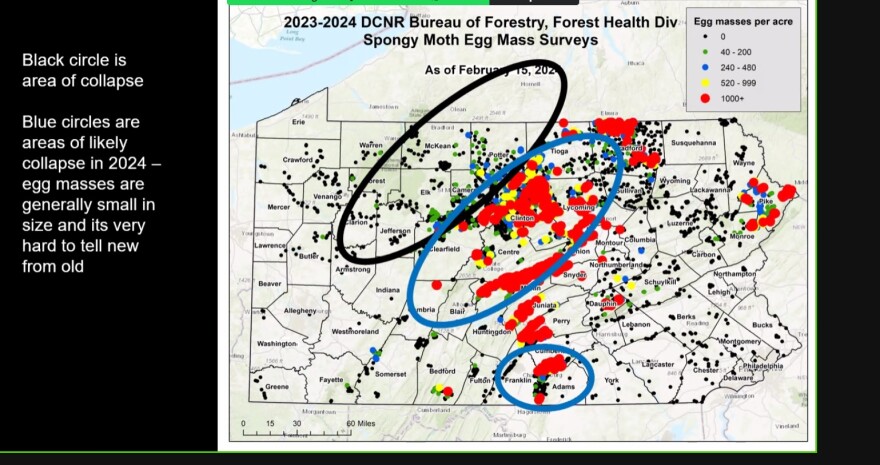

While the highest populations this year are expected in the north-central part of the state, increases have also been reported in northern Dauphin and Pike counties.

“This year is not going to be bad. Probably next year might not be that bad,” Nissen said. “We probably have another two years where things might not be that bad on the Blue Mountain ridge.”

What are spongy moths?

Spongy moths, formerly known as gypsy moths, are native to Europe, brought over to the U.S. in 1896 for silk production, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In 1932, they were reported in Luzerne and Lackawanna counties, according to the state Game Comission.

As a caterpillar, the spongy moth has a yellow and black head, and a hairy body with five pairs of blue spots followed by six pairs of red spots.

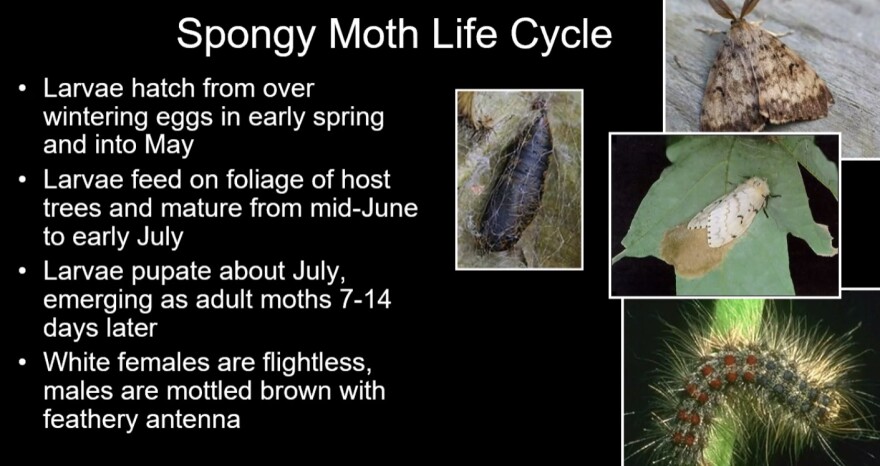

“The larvae, which are the caterpillars, hatch from the overwintering egg masses in early spring and into May — that depends on latitude and elevation when that hatch occurs,” said Sarah Johnson, forest health specialist with the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. She, along with Calvin Norman, a Penn State assistant teaching professor, led a webinar earlier this week called “Frontiers in Forest Health: Managing Spongy Moth.”

“The larvae will then feed on the foliage of their host trees and matures through their series of instar [or developmental] stages from about mid-June to early July,” she said. “They mature in that late June timeframe and then there'll be pupating in July.”

When they reach maturity, females are white and flightless, while males are darker brown. Females can lay between 600 to 1,000 eggs in a compact, tear-dropped shaped mass of eggs and silk, often found high up in a tree’s canopy.

The caterpillars will dine on more than 300 species of trees and shrubs, but seem to prefer oaks, according to the USDA. Left unchecked, an infestation can defoliate up to 13 million acres of trees in a single season.

In March 2022, the Entomological Society of America adopted the new name, citing the former’s use as a derogatory term for the Romani people.

"Lymantria dispar is a damaging pest in North American forests, and public awareness is critical in slowing its spread,” said Jessica Ware, the society’s president, in a news release announcing the change. “'Spongy moth' gives entomologists and foresters a name for this species that reinforces an important feature of the moth's biology and moves away from the outdated term that was previously used.”

Treatments, prevention

In the Valley, spongy moths have been an issue for decades. However, there could be a few reasons why the region isn’t currently experiencing an outbreak.

“We've had, the last few years, wet springs and that brings out a native natural fungus that can really hurt the spongy moth population,” Nissen said, adding that the insects also seem to reach outbreak levels every eight or 10 years. “I think it could be a combination of those two things.”

The fungus is one of the spongy moth’s only natural predators — birds don’t enjoy their texture, officials said.

Near the end of January, state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources officials urged residents to check their properties and plan to treat them, if needed. While state officials last year treated almost 400,000 acres of state-owned land, it's a small percentage of forests across Pennsylvania.

About 70% of all forest lands across the commonwealth are privately owned.

“Private forest landowners play a critical role in assuring the overall health of forests in Pennsylvania,” said State Forester Seth Cassell in a news release. “By opting to treat for spongy moth caterpillars, where necessary, forest stewards across the state can help in the fight against these harmful insects.”

The DCNR plans to treat roughly 228,000 acres this year.

“All through the winter is when you can actually gauge the risk to your trees by looking at how many egg masses you have,” Johnson said. “And then in the spring from hatch through May is when you can do some really effective insecticide intervention. And then, through this July-August timeframe, is when the females on the egg masses are very noticeable on the trees, and the males floating around the trees are also very noticeable.

“If you're vigilant during that timeframe, this is really easy to see — somewhat more easy than just the egg masses.”

Treatment options are limited, but have shown success. The DCNR recommends Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki, or Btk, an insecticide, and Mimic, an insect growth regulator. Both can be deployed through airplane.

However, usually there’s a 50-acre minimum for treatments, experts said. Unless residents can band together with neighbors, they might not meet that threshold. For residents with smaller properties, local arborists can help.

“If it's a good, healthy tree, it can be completely defoliated and the tree’s going to recover. If it gets defoliated year after year, then it’s different story.”Glenn Myster, arborist and owner of Myster Tree and Shrub Service

Glenn Myster, arborist and owner of Myster Tree and Shrub Service in Lehigh Township, said spongy moths aren’t a common issue, but he’s seen the destruction they can cause.

“You have to evaluate it on a case-by-case basis,” Myster said. “A lot of times, I'll tell people if they have a pin oak in their backyard that has gypsy moth, the tree usually recovers.

“If it's a good, healthy tree, it can be completely defoliated and the tree’s going to recover. If it gets defoliated year after year, then it’s a different story.”

In lieu of spraying, there are also sticky barrier bands that can help individual tree infestations.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing readily available to prevent an infestation before it occurs.

“There's not much a landowner can do when we're in a lull,” Nissen said. “And the population rises about every eight to 10 years-ish, and that can vary, but that's that's pretty much a standard.

“We've been in that low now, going on that, so we should expect a spike but they haven't seen any yet. But, as far as what they can do right now, there's not much they can do.”