EDITOR'S NOTE: This is part of our recurring series: Lehigh Valley 250th — a project that examines our region's place and contributions in American history leading up to the nation's 250th anniversary next year.

BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Before there was the Lehigh Valley, there was Lenapehokink, often spelled Lenapehoking — the homeland of the Lenni Lenape.

“It's literally the place where the Lenape are,” Adam Waterbear DePaul, chief storyteller of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, said. “A lot of people tend to translate it, generally, into ‘land of the Lenape,’ and that's OK, depending on how that hits you.

“‘Land of the Lenape,’ meaning the land where you can find the Lenape, is great, but you could also interpret that as, ‘This is the land that belongs to the Lenape,’ and we don't like that interpretation because we did not have a sense of ownership of the land that the Europeans do.

“So, the sentiment that is really portrayed by that word is, ‘This is where the Lenape are, and this is where you will find them,’ not ‘This is their land.’”

For thousands of years, the Lenape were stewards of the mountains, valleys and waterways that make up what residents today know as the Lehigh Valley.

It was only in more recent history, less than 300 years ago, that the indigenous Lenape were renamed the Delaware and dispossessed from the land, driven off by European colonists’ efforts to expand Pennsylvania during the Walking Purchase of 1737.

But, it wasn’t actually purchased, as the name might suggest — it was swindled.

“The Lenape were deceived into agreeing to this. They were manipulated."Steven Harper, professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University

“The Lenape were deceived into agreeing to this. They were manipulated,” said Steven Harper, author of “Promised Land: Penn's Holy Experiment, The Walking Purchase and the Dispossession of Delawares, 1600-1763.”

“And lots of the histories then are quite shocked when the Lenape come back into the Lehigh Valley in the 1750s and 60s and just decimate settlements and take revenge and are furious.

“Finally, there's a peace negotiated in part by Benjamin Franklin and others. And, when the Lenape are asked, ‘What in the world is all this about?’ They are clear that this is about The Walking Purchase fraud.”

‘A devastating piece of duplicity’

While William Penn, the commonwealth’s founder, had relatively peaceful relationships with the Lenape due to his peace-based Quaker religious affiliation, that changed after he died and his sons, particularly Thomas, took over leadership, according to historians.

“They forsake his Quakerism and they gravitate to his materialism. They inherit all of his sense that he owns the place, and none of his sense that he should treat the people who lived there before him as if they also had rights and so forth to the place.”Steven Harper, professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University

“There are ample reasons to blame his sons,” said Harper, whose book was his published Ph.D. thesis dissertation at Lehigh University.

“They forsake his Quakerism and they gravitate to his materialism. They inherit all of his sense that he owns the place, and none of his sense that he should treat the people who lived there before him as if they also had rights and so forth to the place.”

In the years after William Penn’s death in 1718, colonists continued to expand past the northern boundary recognized by both the Lenape and Europeans, the Tohickon Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River in present-day Bucks County.

Thomas Penn and his brothers, saddled with debt, sold tracts of land without any agreement from the Lenape. For example, William Allen, for whom Allentown is named, in 1729 bought 20,000 acres.

Solomon Jennings, one of the “walkers,” in 1736 bought 200 acres of land on the south side of the Lehigh River, in present-day Allentown and Salisbury Township, where Walking Purchase Park now sits.

“Their main motive becomes revenue generation instead of [a] peaceable kingdom,” Harper said.

“Their father wanted a peaceable kingdom, a place where everybody could belong, everybody could have a place, and there would be peace — a godly kingdom. That's not their motive anymore. They want revenue.”

In his book, Harper argues the Penns sold the land without consent from or conversation with the Lenape, an act of duplicity and deception — a fact historians have generally agreed on for decades.

Only after selling the land did the Penns come up with a scheme to take it, citing a treaty from decades earlier, purportedly made between Lenape leaders and their father.

They argued the treaty claimed the land above Tohickon Creek “bounded by a man's walk for a day and a half” had already been bought and paid for by William Penn.

“There was some kind of negotiation between about 1682 to 1686 about purchasing land to the north of that original purchase,” Michelle LeMaster, a history professor at Lehigh University, said.

“Unfortunately, the only thing that really survives in the records is an unexecuted, unsigned deed from 1686. Because it's unsigned and unexecuted, a lot of historians think that it was probably never agreed to by the Delaware, that it was a negotiation that was never brought to a conclusion.

“There is no evidence that any payment was ever made for the land.”

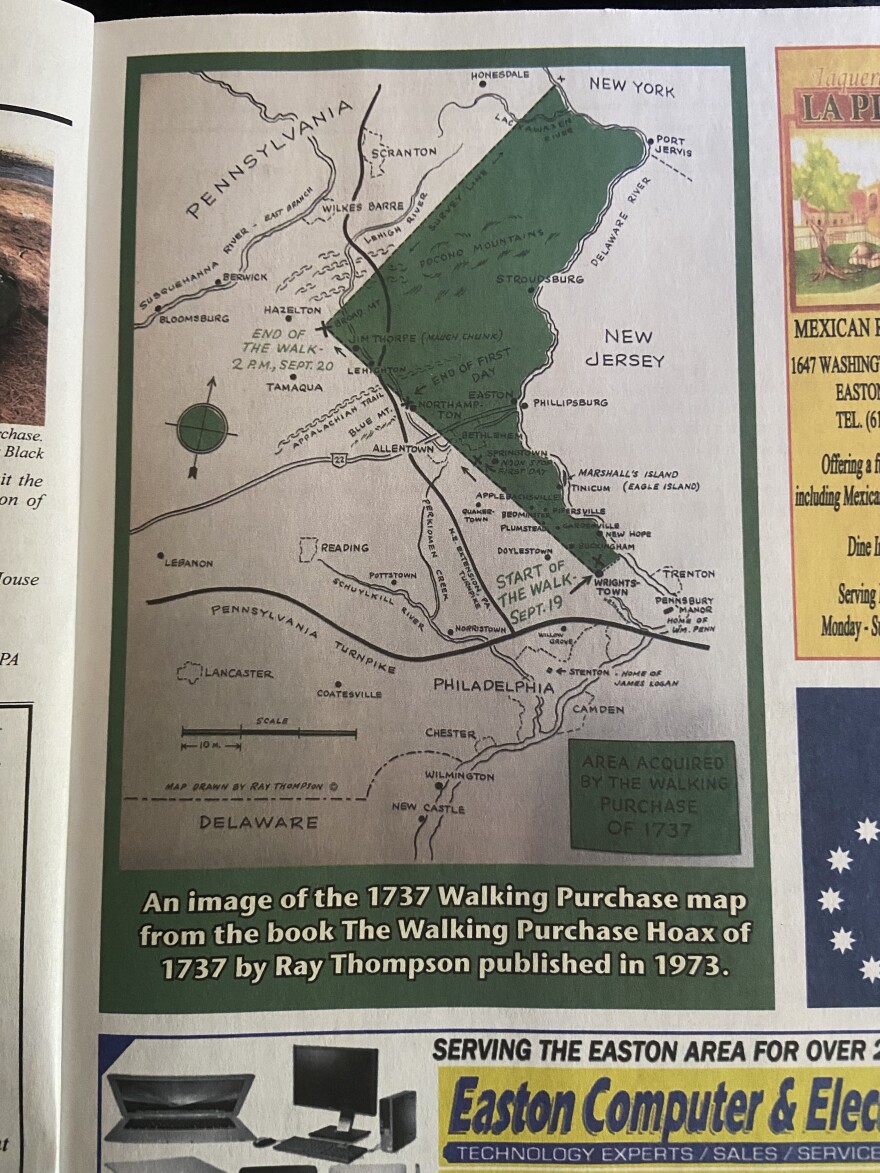

During a meeting between the Lenape and the Penns, the latter say they want to “complete that walk that we started long ago,” Harper said, but produced an off-scale map to illustrate the plan.

“The map is of the Lehigh Valley, but it's much compressed in scale, and it doesn't show Tohickon Creek on it, and it shows the Lehigh River,” Harper said.

“And the Delawares don't read these right. The Lenape don't read these names. They don't know what the names say.”

Leaning on the trust formed through the relationship with William Penn, the Lenape agreed.

The Lenape didn’t know that, in addition to the wrong map, the Penns and their agents had already been hard at work surveying the path they planned to take and enticing volunteers to run the route in lieu of walking.

“The purchase ends up being this triangular shaped piece that's massive by comparison to what the Lenape had been deceived into understanding,” Harper said.

“And the Penns did it on purpose, because they'd already sold the land, much of it in that space, and they needed desperately to get an assurance that the Lenape no longer had rights to it, so that the people they sold it to, the investors, could start making profits off it.

“So, it was just a devastating piece of duplicity.”

And, it was an unusual deal — there aren’t many, if any, other agreements in Colonial America set up quite like it.

“Other land deals usually would be pretty specific about where boundaries would be, and they would send out surveyors,” LeMaster said. “And this is the only agreement that I know of that was based on turning over as much land as a walker can cover in a day and a half.”

‘The Hurry Walk’

In the early morning hours of Sept. 19, 1737, Jennings, Edward Marshall and James Yeates placed their hand on a chestnut tree near the Wrightstown Friends Meetinghouse in Bucks County, officially starting the walk.

The man who walked the furthest would be awarded 500 acres of land.

All three were woodsmen — frontiersmen who knew the landscape, said John Moore, author of “Traders, Travelers and Tomahawks.”

“They knew the terrain; they knew the countryside,” he said. “They knew the roads and the trails, and they knew how to walk over them and how to run over them, if you will.

“ … They would have been used to moving logs and rocks and using axes and hatchets and hammers and moving the things by hand and working with horses and cattle.”

In fact, historical markers often refer to Marshall as "fleet-footed" or "fleet-footed youth."

Historical accounts show witnesses for both sides were present to ensure the agreement was followed, and the Lenape complained when the trio began to move much faster than anticipated.

“They go not parallel to the Delaware, they go away from it at about a 45 degree angle,” Harper said. “And then they walk for a day and a half at a pace that's well over four miles an hour. They couldn't have walked the whole way. The Lenape called it ‘The Hurry Walk.’”

Jennings dropped out, exhausted, before noon on the first day.

The group continued on before stopping in present-day Hellertown for a break, and ended the first day at the Hockendauqua Creek near present-day Northampton Borough.

While Yeates quit the second day, Marshall continued on, “walking” all the way to present-day Jim Thorpe.

“And when they get to the end of the walk, they turn a survey line, not at a 90 degree angle to the [Delaware River], but at about a 45-degree angle,” Harper said.

All in all, Marshall walked about 65 miles.

The exact amount of land seized by the Penns is up to interpretation, as land-measuring practices have changed over time. Generally, historians and officials say either 1,200 square miles or about 1.2 million acres — about the size of Rhode Island — were taken from the Lenape.

The Lenape protested, but were quelled by the Iroquois, a neighboring tribe that sided with the Penns. For completing the walk, Marshall was granted 500 acres of land near present-day Portland at the northern tip of Northampton County.

That trusting relationship nurtured by William Penn was irreparably broken, and colonists paid the price. Marshall’s family was attacked at least twice, ending in the deaths of a son and his wife.

The swindle paved the way for more settlers to move in, shaping the Valley into what it is today.

Scott Paul Gordon, Lehigh University professor of English and an avid researcher of Colonial-postcolonial studies and Moravian history, said the Lenape were probably dispossessed of the land slowly as pressure increased from colonists.

“I'm not even sure we know how many indigenous people, Delawares, were here,” he said. “They largely moved from, I guess you'd say west [New] Jersey, across the river, and then The Walking Purchase compelled them to move further.”

Four years after the “walk,” Bethlehem was founded by the Moravians after the group purchased a tract from land speculators.

“Their land purchases are only possible because of The Walking Purchase,” he said. “None of those people would have purchased that land or been able to flip the land to the Moravians if there were indigenous claims on that.”

A healing journey

In 2019, the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania held a “Walking Purchase Healing Journey,” retracing the route traveled centuries ago.

It started with a “kind of harebrained idea” in an attempt to learn more about, and even somewhat experience, the history of the region, said Christopher Black, artistic director of the Bachmann Players.

“The tragedy of The Warking Purchase doesn't reach its full arc of understanding unless you understand what William Penn did and tried to do and was successful in doing,” Black said.

“His relationship with the Lenape was legit – he kind of adored them, and they kind of adored him, and it was respectful. It was 70 years of peace that almost nobody else could pull off.

“So it's the contrast of that trust and that sort of almost love with his sons, mostly Thomas, who really cheated the Lenape on purpose that makes The Walking Purchase so unfortunate.”

Members of the nation and the players would travel the route, stopping at historical markers and places of interest, acting out the history and including ceremonies to heal the land.

After taking the idea to DePaul, he also presented it to the council of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, who gave their blessing, as long as “it is healing and educational,” he said.

The “Walking Purchase Healing Journey” took place Sept. 21, 2019.

However, to complete the route in one day, the group drove in lieu of walking. There were six stops, from the Wrightstown Friends Meeting House to a farm in Jim Thorpe.

“Everybody had a different takeaway, but I would say, I think everybody thought it was worthwhile,” Black said.

Barbara Bluejay Michalski, chief keeper of culture for the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, described it as a “tough day.”

“It made us understand what our ancestors went through, but it was really, really a heavy day on our hearts, but I'm glad we did it because we needed to heal the land,” she said.Barbara Bluejay Michalski, chief keeper of culture for the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania

“It made us understand what our ancestors went through, but it was really, really a heavy day on our hearts, but I'm glad we did it because we needed to heal the land,” she said.

“So, it's not something you want to make an annual event, because it's very painful, but I'm glad we did it, because it brought awareness about what happened to our people.”

For DePaul, the point wasn’t to re-open old wounds, or place blame on current residents, but to acknowledge the event happened in the first place.

“We have no desire to make people feel bad for what their ancestors did. We don't see that as being helpful at all,” he said.

“ … Everybody needs to be comfortable enough with themselves in the present to acknowledge that whether it's their family or their religion or their institution or whatever, has done some terrible, terrible things in the past.”

While active in the Valley since the late 1990s, the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania is not federally-recognized. It operates as a nonprofit, with a cultural center at 169 Northampton St. in Easton.

Currently, there are three federally-recognized Delaware tribes in the United States, including: the Oklahoma-based Delaware Tribe of Indians and the Delaware Nation, as well as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, in Wisconsin.

The Delaware Nation declined to comment for this story. A request to the Delaware Tribe of Indians was not returned.

“We survived here by assimilating, by hiding, and we made every effort to get off of the record as a matter of survival, in addition to our own efforts to try to keep our heads down."Adam Waterbear DePaul, chief storyteller of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania

“We survived here by assimilating, by hiding, and we made every effort to get off of the record as a matter of survival, in addition to our own efforts to try to keep our heads down,” DePaul said.

“ … So that's the reason that of our state recognized, or unrecognized people here, in our homelands, none of us will ever get federal recognition because we got off and also were erased from that documented record.

“That's a phenomenon we tend to call documentary genocide.”

In neighboring New Jersey, state officials have recognized three tribes: the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation, the Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation and the Powhatan Renape Nation. None are federally recognized.

The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania is currently seeking state recognition, which could open the group up to educational and cultural funding opportunities, as well as having standing when state officials work through environmental issues and solutions.

The group currently has a Change.org petition with more than 14,000 signatures, urging state legislators to recognize it.

‘William Penn and his heirs were sovereign’

Twenty years ago, there was an effort from the Delaware Nation, which claimed ownership of land in Northampton County.

From 2004 to 2006, the Delaware Nation unsuccessfully sued for land granted to Chief Tunda Tatemy, for whom Tatamy is named, the year after the Walking Purchase.

Tatemy, while not centrally involved in The Walking Purchase, was a messenger and interpreter who often helped the Penn family. Baptized “Moses,” he in 1738 became the first private landowning indigenous person recognized by the Pennsylvania government.

The nation sought 315 acres of land in Forks Township, formerly known as “Tatamy’s Place,” according to the initial civil complaint the Delaware Nation filed in January 2004 in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

That district oversees federal court cases in Berks, Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Lancaster, Lehigh, Montgomery, Northampton and Philadelphia counties.

There were dozens of defendants listed, including the state, Northampton County and its council members, as well as residents and businesses, like Binney & Smith Co., the former name of Crayola.

In the complaint, the nation argued a year before Tatemy died, in 1760, William Allen illegally crafted a deed conveying the land to Henry and Mathias Strecher.

“The conveyances and partitions set forth in the deed from Mr. Allen’s estate to Mr. Stretcher’s descendants are contrived, invalid and illegal attempts to convey Tatamy’s Place under color of law,” according to the complaint.

The nation cited the Trade and Intercourse Act, a 1799 law that created a legal framework for land transactions between colonists and indigenous people.

“Because of the absence of any conveyance from Chief Tatemy to William Allen, the Indian Nonintercourse Act dictates that title remains in Chief Tatemy,” according to the complaint.

While the complaint does not explicitly mention how the land would be used if granted, news reports from the time – both from the Poconos and Oklahoma — showed the nation planned to build a casino.

Their suit was dismissed in November 2004. Among the reasons cited was that “The Walking Purchase extinguished aboriginal title,” according to court records.

The nation appealed to the Third Circuit Court, which upheld the lower court’s ruling. Then, the nation appealed again, to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“There is no reasonable question that William Penn and his heirs were sovereign, with authority to terminate aboriginal title during the Colonial period."Gov. Ed Rendell, in a brief opposing the appeal to the Supreme Court

In a brief written by then-Gov. Ed Rendell opposing the appeal to the Supreme Court, he argued:

“There is no reasonable question that William Penn and his heirs were sovereign, with authority to terminate aboriginal title during the Colonial period.”

“Were this not the case, title to all land acquired by William or Thomas or any other Penn — millions of acres — would be undermined.”

In November 2006, the Supreme Court declined to review the case, ending the appeals process.

The Fourth Crow

The legacy of The Walking Purchase is still illustrated across the Lehigh Valley — from the historical markers that dot the landscape, to art and even municipal names originating from the Lenape, like Tatamy, Catasauqua and Hokendauqua.

There are a handful of historical markers along the route of The Walking Purchase, many with towering stone obelisks displaying placards describing the event.

One marker in Kreidersville reads, “Measured 1737, according to a supposed Indian deed of 1686, granting lands extending a day-and-a-half walk. Using picked men to force this measure to its limit, Thomas Penn reversed his father's Indian policy, losing Indian friendship.”

There are three markers related to The Walking Purchase currently missing, all near Jim Thorpe, including the sign that marked the event’s terminus.

Asked about the status of those missing markers, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission’s historical marker coordinator, Alli Davis, said the commission “is committed to replacing up to 10 missing markers each year.”

“With more than 2,500 markers across the state — and over 500 currently known to be missing — it will take time to address them all,” she said.

“We review the list of missing markers once a year to decide which ones to replace. Public requests are given priority in that process, though newly approved markers are ordered before replacements.”

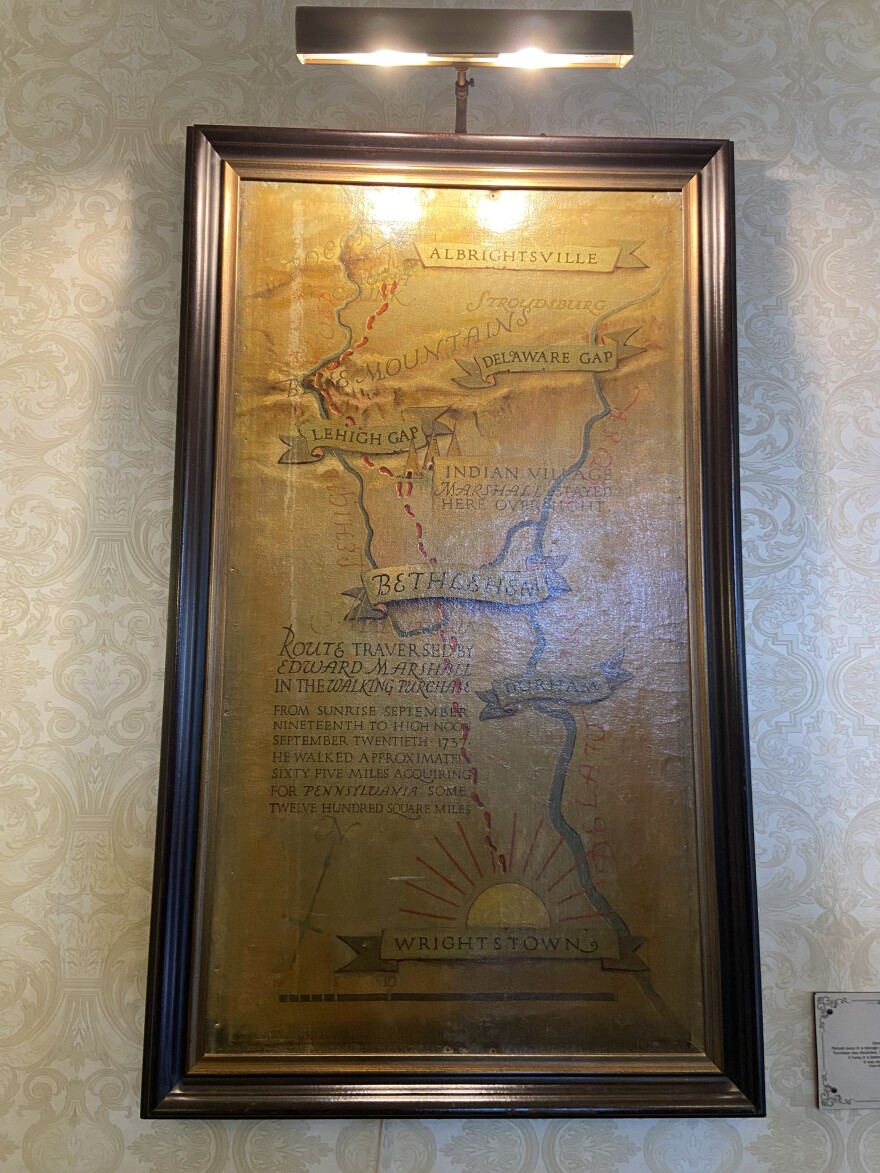

At the Historic Hotel Bethlehem, 437 Main St., there are not one but two murals depicting the event.

“The Walking Purchase” and “The Lost Mural” were both painted in 1936 by George Gray, part of a collection of oil paintings depicting historical events that occurred in the region.

It’s the only hotel that retains its set of murals by Gray, who created 233 murals for hotels across the United States in the 1930s and '40s.

“The Walking Purchase” is a four-foot by nine-foot painting depicting Edward Marshall walking through the woods as four agents and a single Lenape look on. It hangs in the hotel’s Mural Ballroom.

Hanging outside the ballroom, however, is a much smaller painting, showing the map of the route.

This painting was dubbed “The Lost Mural,” because it was found packed away in a storage closet and saved from the trash by an employee. It hung in a basement office for a half-decade before it was recognized as one of Gray’s paintings.

And, a new art exhibition focused on the Lenape recently opened at Northampton Community College’s Dunning Gallery at the Pocono Campus in Tannersville.

"Enduring Presence 2025: Art of the Fourth Crow," includes both contemporary and historic art, as well as functional objects from the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania. It runs through Dec. 6.

According to a Lenape legend, a fox “would be loosed upon the Earth,” but that four crows would also come, DePaul said.

“The first crow flew in harmony with the creator,” DePaul said. “The second crow tried to clean the world, but he became sick and died. The third Crow saw what happened to his brother, and he hid.

“The fourth crow will fly in harmony with the creator again, and caretakers will live together on the Earth.”

The story has become a symbol for the Lenape and their history, he said. The first crow represented harmony before Europeans arrived, the second was initial contact with the colonists, and the third symbolized the period where indigenous culture was suppressed entirely.

While it’s up to interpretation, many believe it’s now the time of the fourth crow, when the Lenape can live on their lands in harmony again.

“The story is linear. It's not circular,” DePaul said. “The harmony of the fourth crow is a new harmony. There's no going back to the first crow — that crow has flown.”

The fourth crow, rather, signals the end of the third, ushering in a new period of peace.

“Where we can actually come out of hiding and say, ‘Hey, we're still here. We've been in the homelands all this time. You just erased us in the documents and then forced us into hiding, or absconded us into the boarding schools.’

“But we're still here, and we want to welcome everybody who is here in goodwill — individuals who had no business, no part in the times of the second and third crow, and all of us create a new harmony and move forward in a good way with our neighbors.”

CHECK IT OUT: "Enduring Presence 2025: Art of the Fourth Crow," is on view at NCC's Pocono campus, 2411 PA-715, Tannersville. Regular gallery hours are 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. Mondays through Thursdays; 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Fridays; and 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays.