BETHLEHEM, Pa. - For those less immersed in the hows and whys of weather, the probability of a winter storm rolling through the area can appear to be laid out by forecasters well in advance.

- For the average person, the weather seems like something that experts know in advance

- This includes extended outlooks, probable paths and what might put a winter storm on a collision course with the Lehigh Valley

- However, seasoned meteorologists actually shy away from longer-range winter storm outlooks

They’ll talk about extended outlooks, probable paths, the vagaries of the atmosphere and what might put a winter storm on a collision course with the Lehigh Valley and the rest of the mid-Atlantic region.

The only problem?

A 10-day or even 5-day tracking period does not have a reliability (read: accuracy) that people can count on, said a number of meteorologists interviewed by LehighValleyNews.com.

In fact, those forecasters say the time of year makes it even more difficult to predict exactly what winter storms will bring — sometimes right up until their arrival.

“So, the seasonal transition is a big thing as we head into winter,” EPAWA meteorologist Bobby Martrich, a private forecaster based in Whitehall Township, said.

“It’s the same thing that happens when we're going from winter to spring, especially with the model guidance we use. It has a tendency to rush changes, and we saw that play out with the pattern change that we’ve been looking at since the beginning of November."

That pattern change involved a Greenland Block that began to supply the region with one key ingredient needed for snow storms — cold air. But a source of moisture also is necessary for clouds and precipitation to form — and that moisture has to meet the cold air at the right time, and in the right place, for winter storm formation.

It’s why many seasoned meteorologists shy away from longer-range winter storm outlooks. Because even if storms are to the point they can be projected weeks out — in a very broad context — the models used can't possibly pinpoint where and when precipitation will fall, how much or what type can be expected, or how intense a storm might be.

“The issue is that it’s one model run in a sea of model runs that people are looking at and sometimes sharing,” said meteorologist John Homenuk, a lead forecaster for Empire Weather and NY Metro Weather.

“Of course, we have this insane ability to focus in on high resolution graphics now, so I think that has changed things a lot, because everyone has access to them.

“But to me, I definitely think the models have gotten a little more unstable, as well. I feel like they’re a lot more sensitive to changes, especially with these big storms, and it seems like the models just jump all over the place.

“Even in the days leading up to the event, they’re so hectic and volatile,” he said.

'The biggest thing... is always transparency'

Matthew Cappucci, an atmospheric scientist and meteorologist featured in a variety of media outlets (Fox 5 DC, The Washington Post, MyRadar Weather), is anxious to tell his ever-widening audience all about the weather.

But the one thing in which Cappucci is not interested is floating a storm signal just to be first with the information.

“I think the biggest challenge for me is that I would rather be right than be first,” Cappucci said. “In this day and age, some [people] care who has a decent forecast that is out first. But I will never sacrifice my values as a forecaster by working ahead of a goal — and that is making a scientifically specific forecast.”

Cappucci said there are forecasters who “want to put the big business out there” but are doing it deterministically, providing only one single solution, and ignoring the fact that the slightest variations in storm track, temperatures, moisture and other variables can lead to vastly different outcomes.

When they share those types of forecasts, including those with scary model charts or plots, Cappucci compares it to trying to sell an audience "magic beans."

There could be a storm a week from now.

— Matthew Cappucci (@MatthewCappucci) December 16, 2022

COULD

That’s all. Maybe. Maybe not.

ANYONE who peddles a specific forecast with scary model charts or plots is selling you magic beans.

We can give you probabilities — odds — but that’s all. Odds are higher for snow. @MyRadarWX pic.twitter.com/f0ikjDFDsR

“I want to explain to my audience exactly what the options on the table are,” he said. “So, seven to ten days out, I can look at a broad pattern and gauge the big picture players.

"But I’m talking about a big, broad picture. Then five to seven days out, I look at the ingredients that will support a storm. Because maybe they’ll link up, maybe they won’t. But the one thing I cannot offer is precipitation estimates.

“Finally, two to three days out, I can start putting out rough snowfall maps. How much snow can we expect? But on the day of, I can resolve mesoscale factors — county to county where the biggest snow band of the day might set up, or who might get less than expected.”

But the most important job, Cappucci stressed, is being as clear as possible.

“The biggest thing for me is always transparency,” he said. “Because we rarely have a great idea of what a storm will do until about three days out, when the instigating energy will move over the Pacific Northwest and can be sampled by weather balloons.

"Prior to that, different models ingest and interpolate [smooth] already-sparse observations in slightly different ways — which means we have different initial conditions, or starting points, for the models.”

Location, location, location

To make forecasting in the area even more difficult, the Lehigh Valley is in a transition zone where a good old-fashioned snow storm is no guarantee.

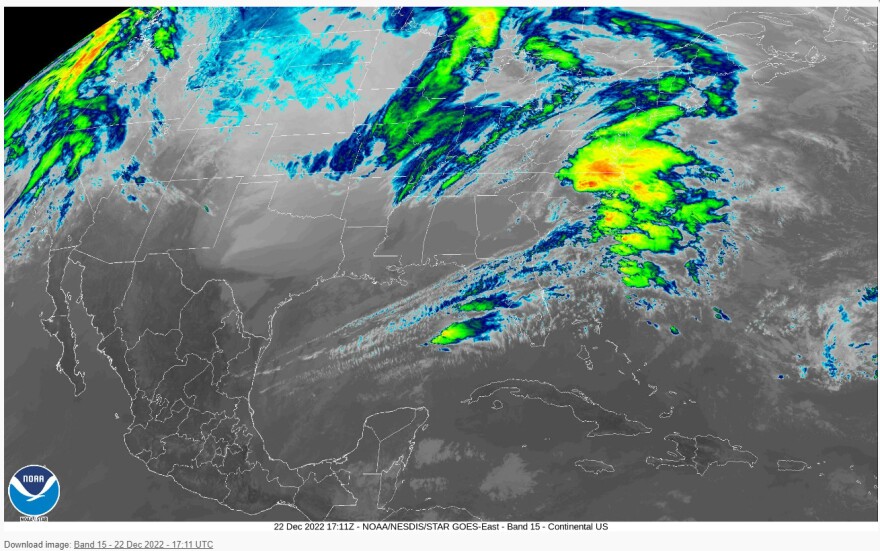

Just like the storm that rolled in at the end of the week, there were downpours for many, a wintry mix for some and bitter cold temperatures that followed.

“The biggest challenge for me is that we obviously have changes in elevation — there's one just northwest of I-95, and they call it the fall line,” Martrich said. “So I-95 is a pretty good marker for where a lot of times in winter, you'll see, OK, well northwest of I-95 is gonna get snow, but in the southeast it’s going to be rain.

“That usually ends up being a marker, because of the elevation change,” he said. “We also have another elevation change, when you go to the Blue Ridge, when you get up there to the Poconos versus here. So elevation change is probably our biggest challenge here in this region.”

To that end, it’s not uncommon that we see what appears to be a near-perfect storm track for snow but still end up with a wintry mix or rain, even in the middle of winter.

Homenuk said some of the area’s most memorable winter storms have featured strong high pressure to the north, which pumps in arctic air. Ideally, it’s locked in place over eastern Canada a day or two before a coastal storm develops.

Without the high pressure in place, it’s rare for the Lehigh Valley to receive a heavy snowfall, as it sits on the “warm” side of the storm. Instead, we get a cold rainfall with temperatures hovering just above freezing.

“There's warmer waters, ocean waters, currents that the storms are tapping into,” Homenuk said. “So, you know, it seems like we when it comes to winter storms, our job is only going to get more difficult. That's kind of the resounding thought that we have.”

When forecasts go awry, all of these forecasters said it’s important to learn from and to acknowledge.

“Being in the limelight takes a certain level of confidence,” Cappucci said. “I think for a lot of people, confidence and ego sort of blend. I promised myself I would never not say when I was wrong. In admitting when I’m wrong, people appreciate that.

“There’s nothing that frustrates me more than a meteorologist that has no rear-view mirror. We have to look back and see what went wrong.”