BETHLEHEM, Pa. — A Lehigh Valley native known for her tornado research now has a credit on the summer’s biggest blockbuster.

Jana Houser, who grew up in the Emmaus area, was a consultant on “Twisters,” the flick that blew through the box office on its opening weekend, grossing $80.5 million in North America.

The movie bowed in 4,151 theaters in the United States, becoming the top domestic opening ever for a natural disaster film, not adjusted for inflation, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

On top of that, “Twisters” raked in $42.7 million more at the international box office, for a worldwide total of $123.2 million.

Houser, who ultimately spent a week chasing storms with a Los Angeles film crew for “Twisters,” said the brush with Hollywood may have been decades in the making.Jana Houser

Natural disaster films always are big business in Hollywood, and “Twisters” — a reboot of the 1996 film “Twister” — has been no exception.

It arrived in a new era of fascination for a weather phenomenon scientists still are working hard to figure out.

Houser, an associate professor of meteorology at Ohio State University, has been a leading voice in that community.

She’s authored or co-authored dozens of peer-reviewed journal articles related to tornadoes and supercells, and has spent decades chasing violent atmospheric storms.

In 2018, her analysis of tornadoes and the supercell thunderstorms that produce them challenged existing assumptions about how tornadoes form: from the bottom up, not the top down.

But Houser, who ultimately spent a week chasing storms with a Los Angeles film crew for “Twisters,” said the brush with Hollywood may have been decades in the making.

Riding inside a TIV

“Way back in the day when I was still an undergrad at Penn State in 2004, it was the very first time I was ever out in the field,” Houser said in a phone call Monday.

“I met an IMAX photographer named Sean Casey, and he designed the very first armored vehicle that ever went into or was designed to penetrate tornadoes.

"He put a turret on the top with his IMAX camera and armored it with steel plates, then put a spike system in there so he could drill down and kind of anchor everything.”

“He’s like, ‘I can't tell you what I'm working on, but it's a Hollywood movie, and I need some meteorological support. Would you be interested?’ Like, yes, absolutely. So that was kind of how that whole ball got rolling.”Jana Houser

The rig was dubbed the TIV, or Tornado Intercept Vehicle. A year later, Houser would join the crew for meteorological support.

“It was, ‘OK, well, where do you need to be?" she said. "Where in the storm do we need to be? So I was actually chasing in that vehicle.”

Casey and Houser maintained periodic contact over the years, and reconnected in what she called a “serendipitous” moment.

“Last spring, I just kind of randomly was thinking about him and sent him a text to say, ‘Hey, how are you? What kind of projects are you working on?’” she said.

With the studio on the cusp of announcing “Twisters,” Casey had to keep things under wraps.

“He’s like, ‘I can't tell you what I'm working on, but it's a Hollywood movie, and I need some meteorological support. Would you be interested?’" she said.

"Like, yes, absolutely. So that was kind of how that whole ball got rolling.”

‘The premise … is a real thing’

From “Twister” to “Twisters,” Houser marvels at how the scientific pursuit of storm chasing has graduated from small teams of researchers to a rolling community of thrill-seekers and content creators chasing the next big storm.

It’s something she said she believes the film captures accurately.

“My role in the whole process was to utilize meteorological observations to get us to a position where we could be seeing big storm activity,” she said.

“That meant being as close to any tornado or any potential tornado that I could get us.”

Along the way, she said, her goal was to help make sure the basic science in the storytelling was accurate.

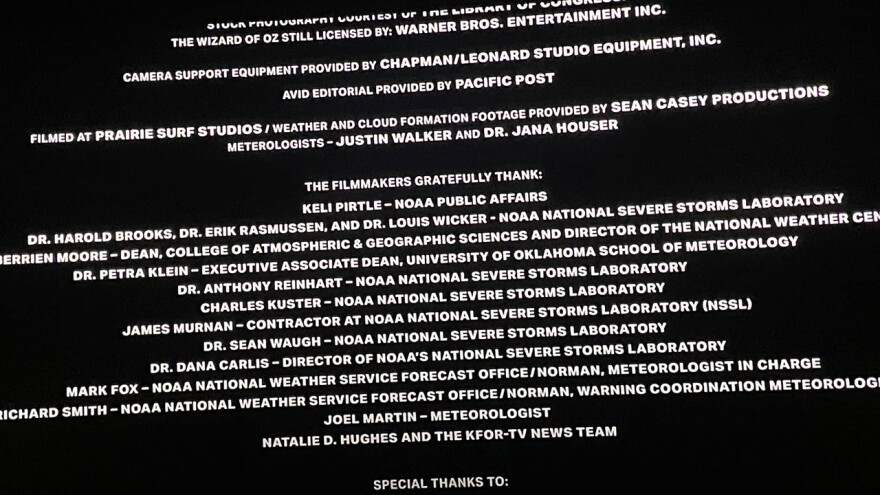

“They did a really good job in terms of doing their research," Houser said. "They had science consultants from the National Severe Storms Laboratory and the Storm Prediction Center and the National Weather Service.

“They had their crew actually go out to the National Weather Center in Norman, Oklahoma, for a crash course in meteorology and severe storms and storm chasing.

"So they did a good job encapsulating certain aspects of chase culture and the science of tornadoes.”

"That’s real. That’s something that I personally have been trying to achieve my whole career.”Dr. Jana Houser on the science of surrounding a tornadic storm

And while the true premise of “Twisters” is an effort by scientists to kill or disrupt a tornado (something that, for now, is a complete Hollywood invention), Houser said she appreciates the larger dynamics at play in the film.

“One of the big things that plays out in the movie is this sort of competition between a group of corporate-backed scientists where the leader does have a true interest in science," she said. "He utilizes a radar technology that is a real thing.

“The premise that he’s trying to investigate or kind of deploy on the tornado is a real thing, which is called Multi-Doppler Synthesis, which is where you deploy multiple radars surrounding a tornado or tornadic storm.

“By viewing the tornado at different angles, you’re actually able to retrieve a three-dimensional wind profile of what’s happening in and around the tornado. So that’s real.

"That’s something that I personally have been trying to achieve my whole career.”

Environmental changes happening

While “Twisters” inevitably takes some creative liberties in its storytelling, Houser said she believes technology will continue to advance to where scientists might one day be able to pull off what is currently only Hollywood fiction.

That being said, there’s a long way to go, she said.

“One of the things that people are exploring now is the use of artificial intelligence and the use of these automated algorithms that take into consideration a huge array of different storm scale attributes," Houser said.

"And then can sort of feed that information to humans to say, ‘Hey, we have something interesting possibly happening here. Focus your attention over here for a moment.'

"We have, at best, 70 years worth of tornado data. So it’s a little bit unclear how what we’re experiencing now fits into the broader, longer term historical context."Dr. Jana Houser

“And so, things like that are kind of just in the sort of early stages of development and of testing in terms of where we need to focus efforts scientifically.

"Because when it comes down to it, our observations will just simply never cut it.”

What Houser wants the public to know is that, despite narratives to the contrary, the idea that tornadoes are getting worse or more frequent is not backed by science.

“When you sort of average everything out across the board, nationally, things are staying pretty similar," she said.

"But you could definitely say the number of most intense tornadoes is at least level, if not slightly declining.

“What we do know is that there are environmental changes happening in terms of the geographic distribution of where and when tornadoes are occurring across the calendar year.

“That extends, although it's not statistically significant yet, but it does extend up into the Atlantic Coast, into New England, into eastern Pennsylvania, down through, you know, essentially, like the plateau in North Carolina into Georgia, et. cetera.

“So all of these areas that traditionally, people have never really worried about tornadoes, it’s possible that we might be seeing an increase in tornado activity in those locations."

The challenge researchers face, Houser said, are tornado records in comparison to a long-term climatology of temperature and precipitation records.

“We have, at best, 70 years worth of tornado data," she said. "So it’s a little bit unclear how what we’re experiencing now fits into the broader, longer term historical context.

"But I think we can, at least in our sort of living memory, get a sense of, ‘Hey, tornadoes seem to be happening more commonly where I’m living.'”