BETHLEHEM, Pa. — Just 20 months ago, Daniel Gwynn was still incarcerated in a Pennsylvania prison, serving a sentence for a 1994 crime he did not commit.

He now goes by “Exonerated Artist 197” — a title that marks his place among the 197 people in the United States who have been freed from death row since 1973.

"It was horrific," Gwynn told an audience of about 50 people at Moravian University on Tuesday.

In 1994, Gwynn was convicted of aggravated assault, first-degree murder and arson.

"They already had a suspect," he said. "They refused to investigate, and I still don't know to this day why or how they chose me."

After he spent three decades behind bars, his case was finally dismissed in February 2024, when a judge granted a motion from the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office to throw out the charges.

Now a free man and traveling the country, Gwynn, a self-taught artist, delivered an emotional presentation, in partnership with Art For Justice, at Moravian's School of Theology's Bahson Center.

Art for Justice supports and exhibits art by incarcerated individuals to open dialogue about reducing incarceration and prison reform.

Gwynn's lecture was part of the School of Theology's new Lifelong Learning series.

'I believed them'

Gwynn was only 24 when detectives took him into a room at a West Philadelphia precinct and told him he had committed the crime.

“I felt like a 9-year-old boy in there with those big homicide detectives,” he said.

“I didn’t know my rights. I believed them.”

After his conviction, Gwynn said, he thought about ending his life.

Instead, help arrived in an unexpected form: Other inmates.

“It gave me a reason to keep going."Artist Daniel Gwynn

One passed him a note showing how to request phone calls, when showers were scheduled, and how to reach the law library.

"Harold Wilson, another exonerated person, told me the first thing that you need to do is you need to write the clerk of courts and get your trial transcript," Gwynn said.

"And go over them, so you can learn about your case, and communicate with your attorney."

He said another inmate gave him paint supplies.

“At first, I didn’t even know how to paint,” Gwynn, who is color blind, said.

“But I was poor. If I could make art, I could sell it to buy soups or writing paper and art supplies.”

With the money he earned, Gwynn launched his own food package program, and sent essentials to elderly, mentally ill and destitute inmates.

“It gave me a reason to keep going," he said.

The road to freedom

At Tuesday's lecture, Gwynn unveiled a collection of paintings he created during his time behind bars.

Arranged in a loose chronology, the works trace his life’s arc — from scenes of a fractured childhood to the legal struggle of proving his innocence.

"Where's Daddy" features a small child clutching a toy phone, waiting for a father who never came.

Gwynn, who said he was raised by his grandmother, said he felt abandoned by his parents.

“He’d promise we’d go fishing or do something together,” Gwynn said.

“I’d sit outside waiting until the streetlights came on. My grandmother would come out and say, ‘Baby, he ain’t coming. Come inside.'”

Gwynn said two of his favorite paintings, "Daniel in the Lions Den" and "Daniel in the Lion's: Den: Daniel Transcends" are inspired by his fear — and faith.

“God broke down the back wall of my prison,” Gwynn said.

“He told me, I’ve been here all along. Now you’re ready. Let’s build you back up.”

He said the lions in the painting represent a man surrounded by danger, yet unharmed, and a man stripped of freedom, yet beginning to rebuild his soul.

'Just keep up hope'

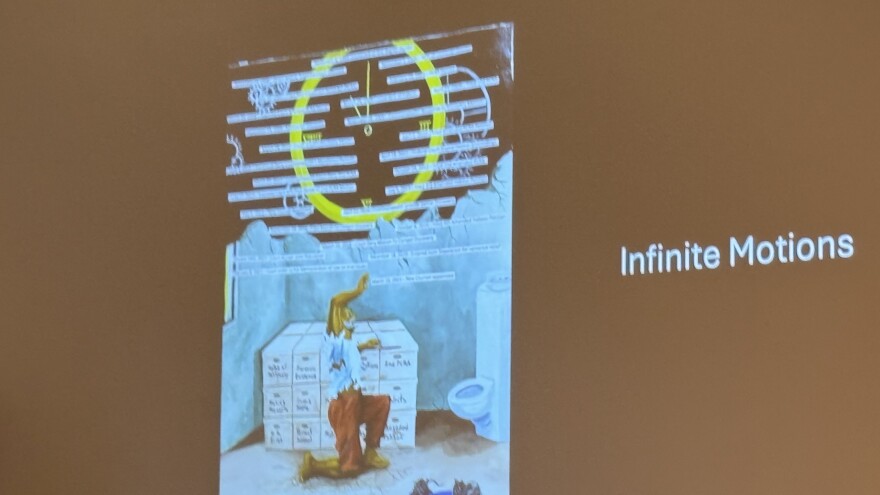

Another painting, "Infinite Motions," speaks of Gwynn's legal studies in prison and constant communication with his attorneys.

In the piece, Gwynn is kneeling next to a stack of boxes as he peers up at a yellow clock.

" All those little scraps of paper you see right, those are all the motions that I filed over the years trying to gain my freedom," he said.

"In death row, they kept us in shackles. Our hands and legs were shackled and they made us strip search and humiliate us — just to go to the shower or the law library. But God said, 'I got this, injustice will be denied, just keep up hope.'"Artist Deniel Gwynn

His "Alienation" depicts a sword-drawn figure inspired by the iconic blind justice figure, with images in the middle of broken chains.

"She's supposed to be blind in her dispensing of justice," he said. "But because of the corrupt system around us, they tried to prevent her from dispensing this justice.

"But she got her sword, and she's bringing all those chains up."

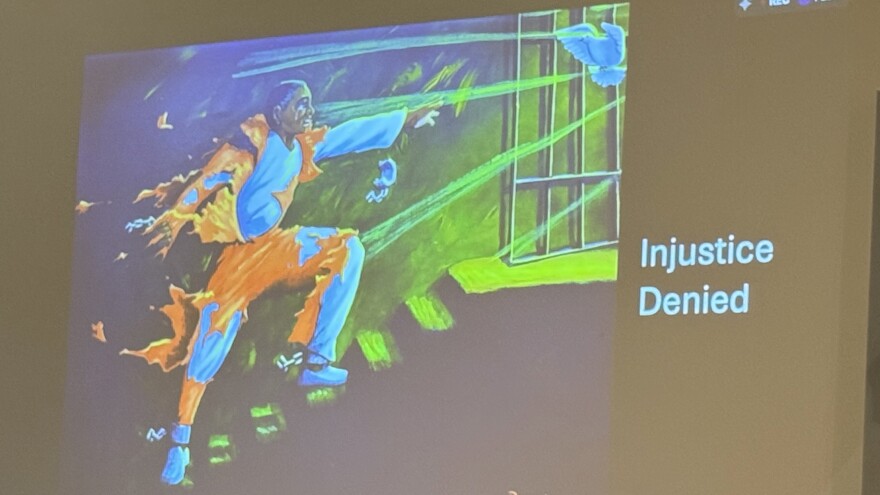

Another equally telling portrait, "Injustice Denied," shows a man in a ripped orange jumpsuit running upstairs toward a white dove, a symbol of freedom.

Underneath the orange jumpsuit, the man wears a white frock — a metaphor for baptism and renewal.

"In death row, they kept us in shackles," Gwynn said. "Our hands and legs were shackled and they made us strip search and humiliate us — just to go to the shower or the law library."

"But God said, 'I got this, injustice will be denied, just keep up hope.'"

'I still have to work'

Gwynn spoke openly about what he lost while behind bars: His grandmother and great-aunt passed away, and he missed years with other family members and friends.

“I lost time I can never get back,” he said.

Through his work with Art For Justice, his art was featured at over 100 exhibits and events.

Gwynn has also shared his art and story with other organizations, such as Compassion and Life Spark, based in Europe.

Even though what he calls a corrupt system failed him, Gwynn said he hopes to get involved with politics one day.

"I'm still healing myself and trying to learn how to make it back into society," he said.

"On the grace of God and a large amount of supporters, I've been able to get my feet on solid ground, but I still have to work on my mental and my heart."

His telling painting "Voting Rights" is a nod to his exercise of his right to hold government offices accountable.

"I was in my cell watching TV, and hearing all these people complain about how the world is so messed up, how their life is so messed up," he said.

"I heard on the news that voter turnout was low. That's the problem right there. No one is coming out to vote.

"As soon as I was exonerated, one of the first things I did was vote."